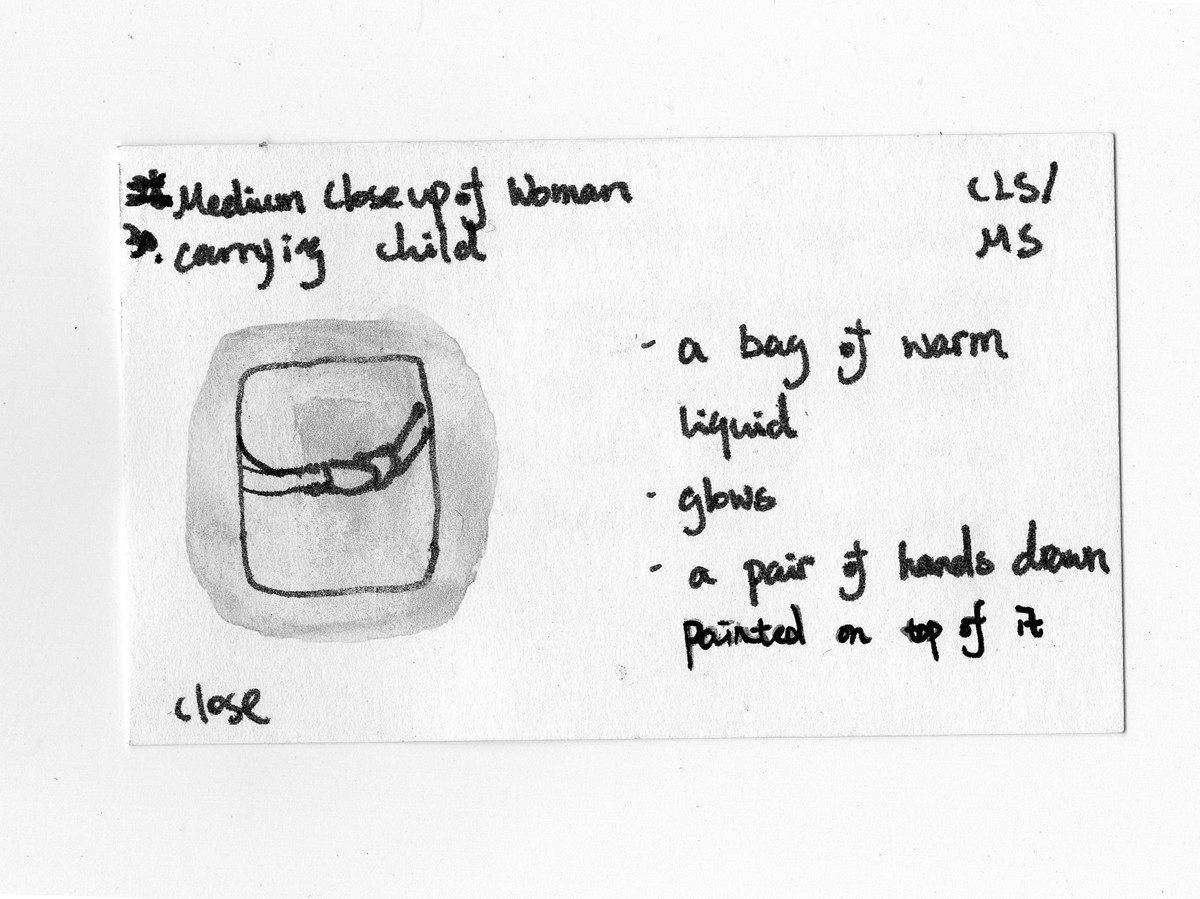

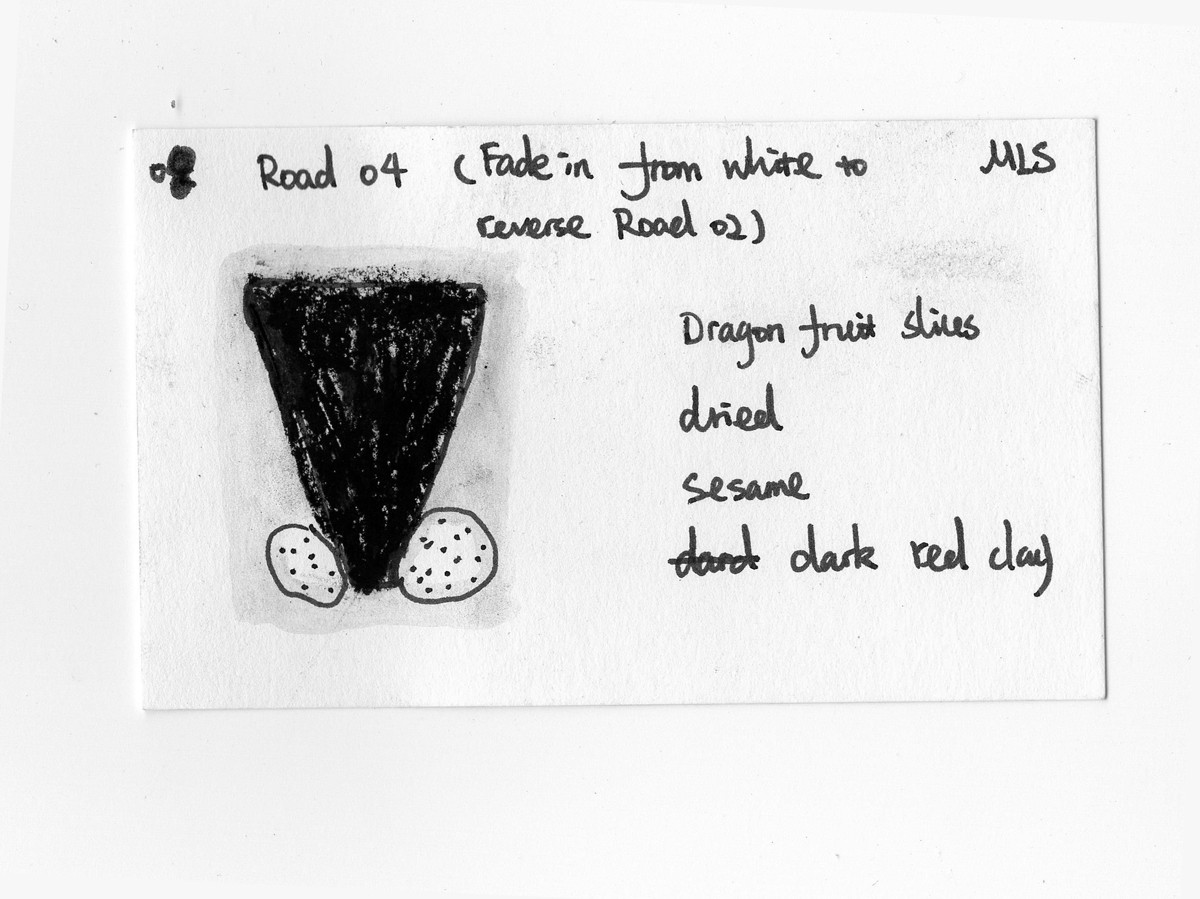

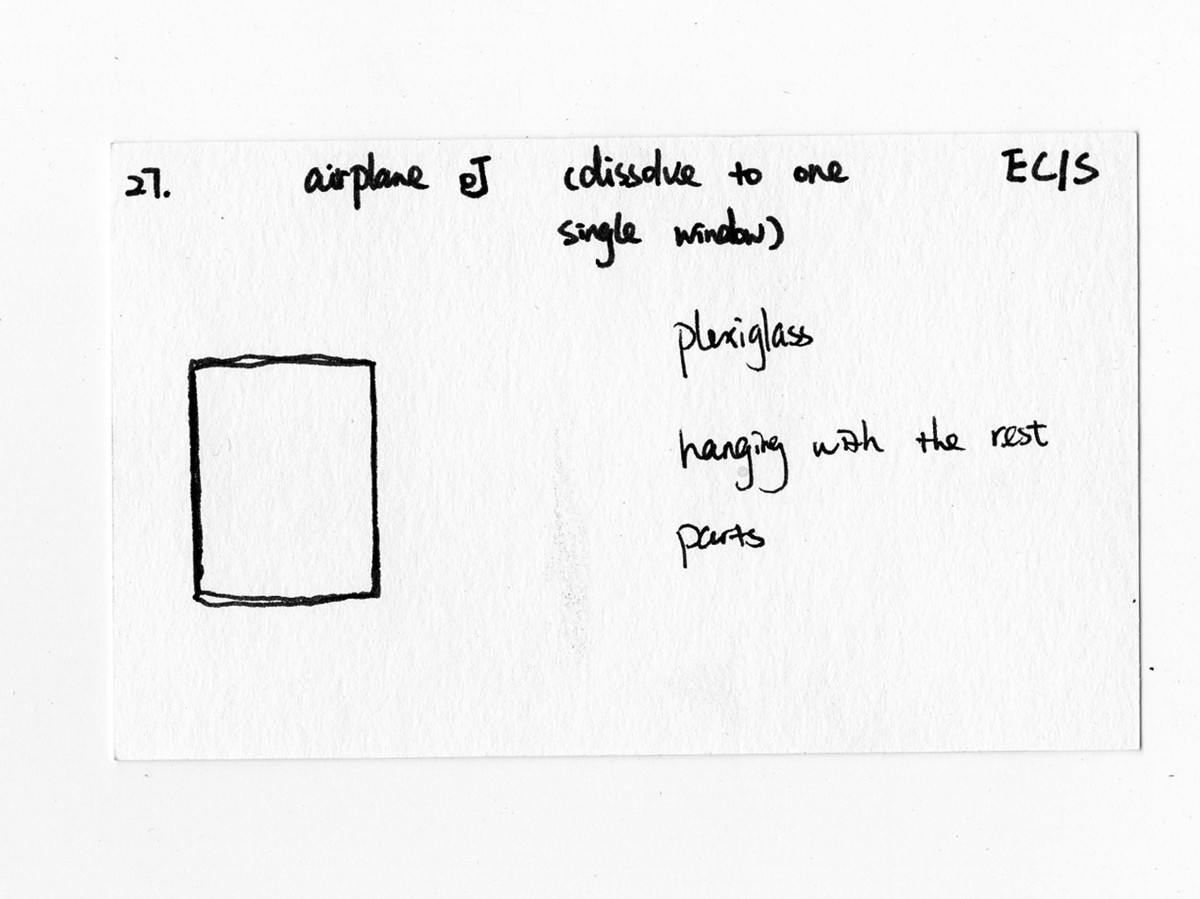

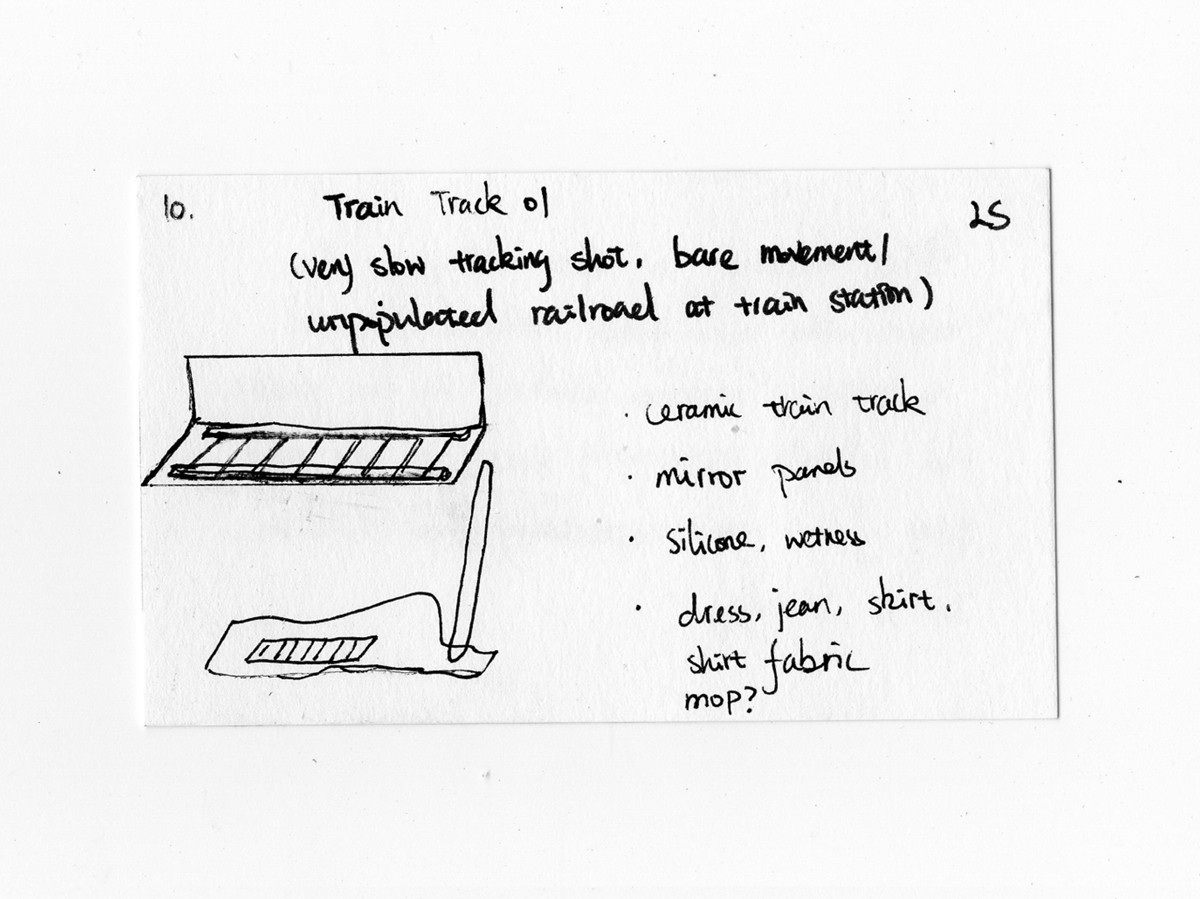

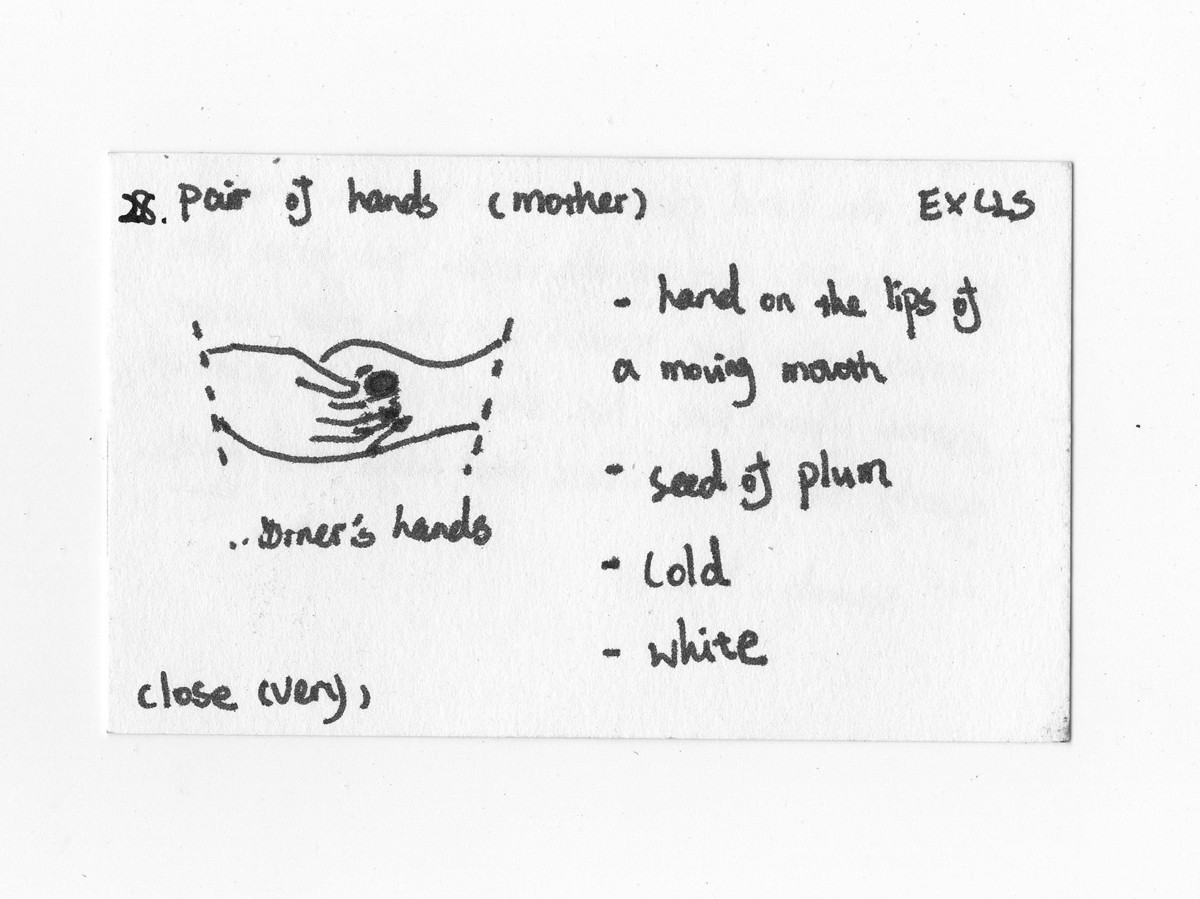

Video element from Upon Leaving the White Dust, 2017/2018

I will give one more example in the work of Cici Wu (born 1989), an artist currently developing a reconstruction of an unfinished film by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-1982).

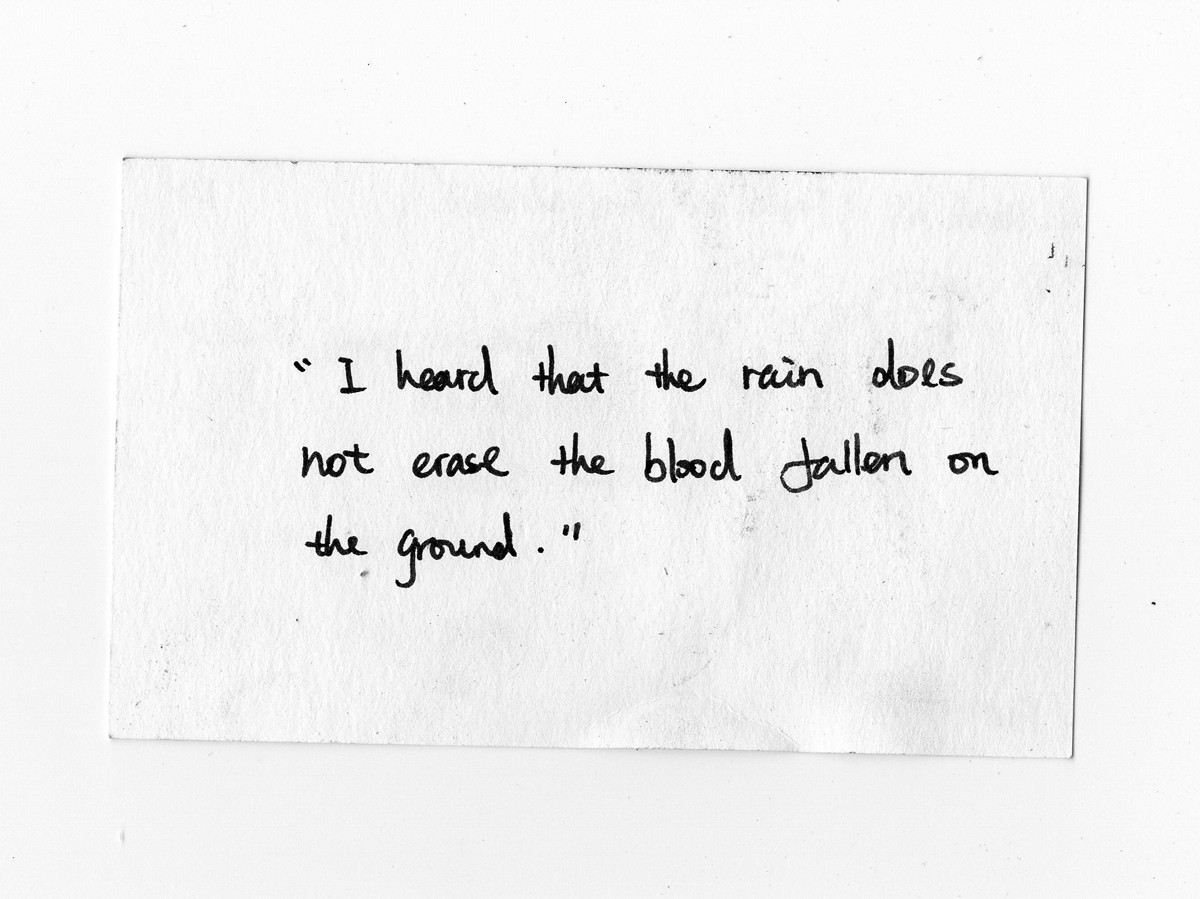

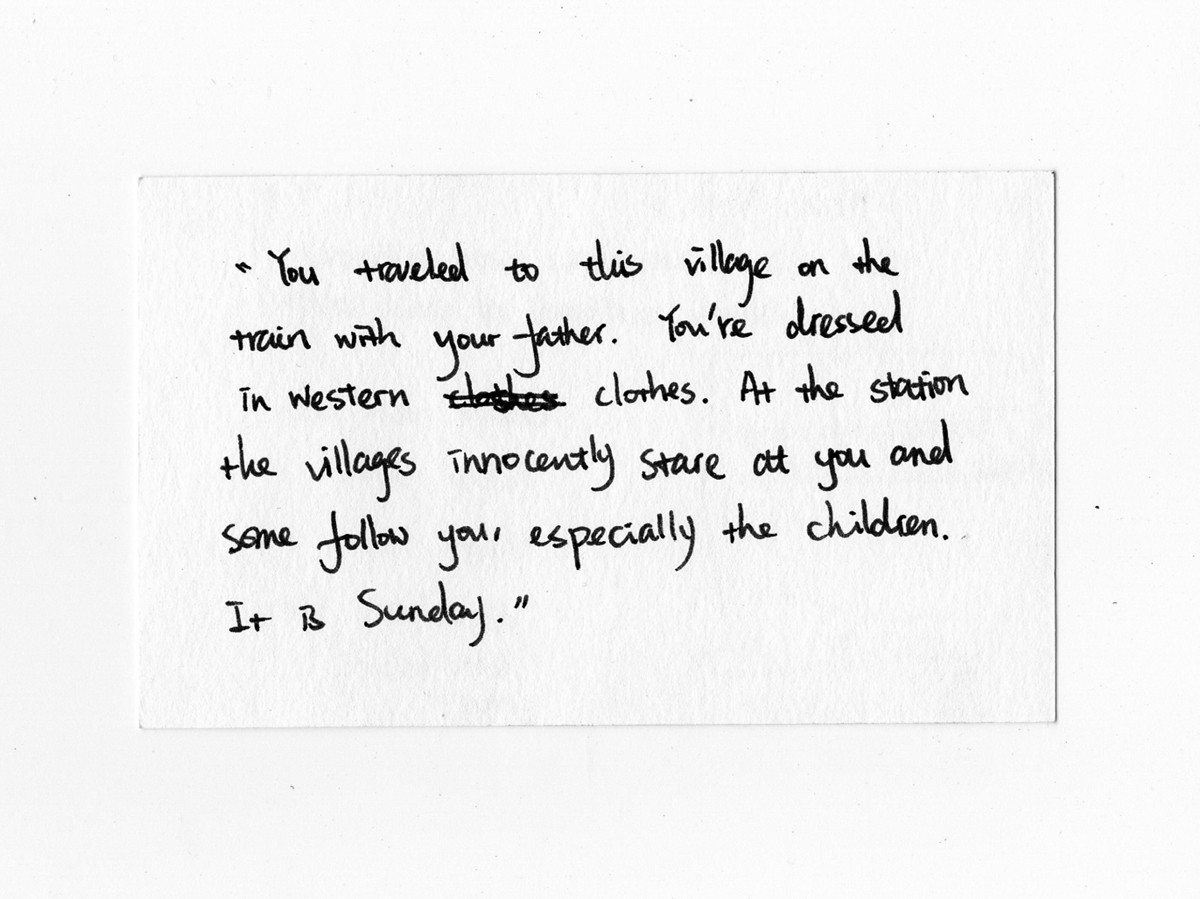

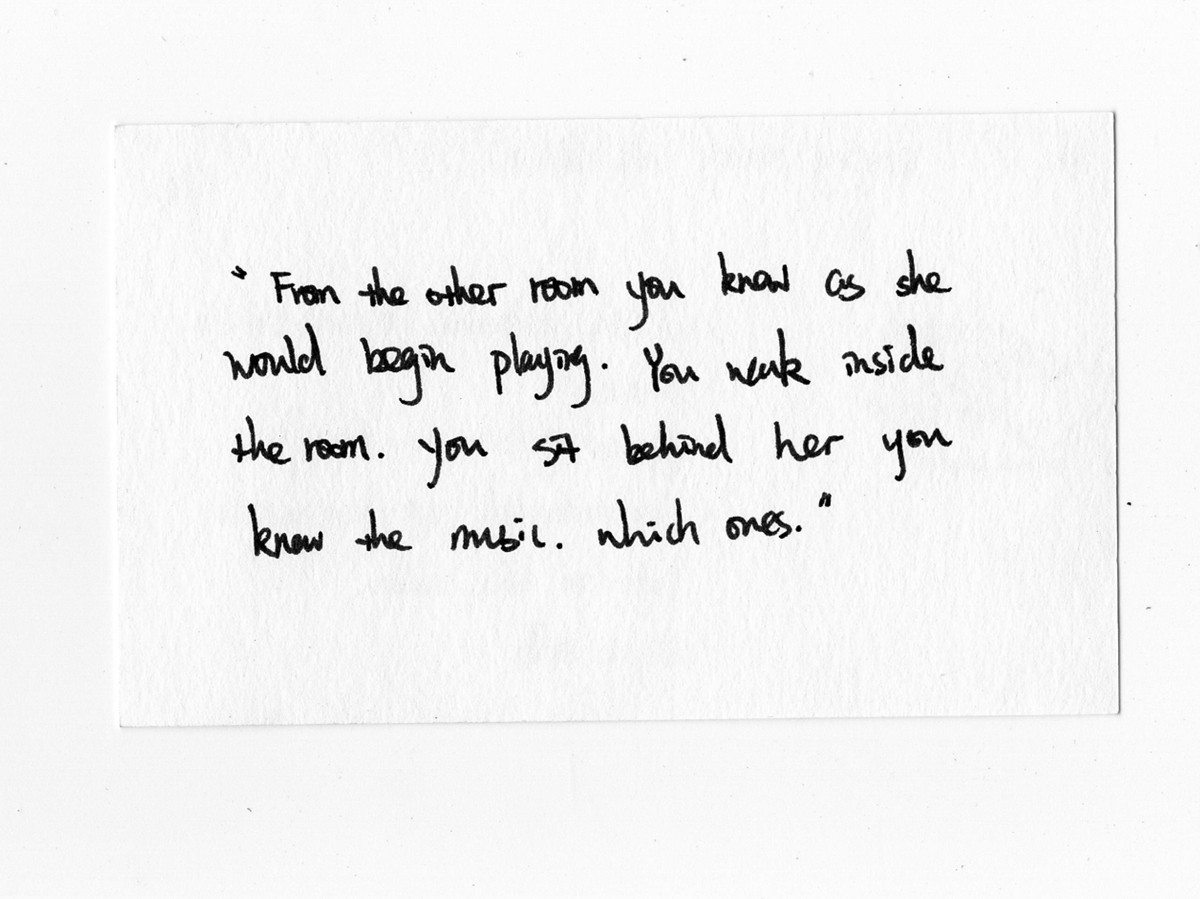

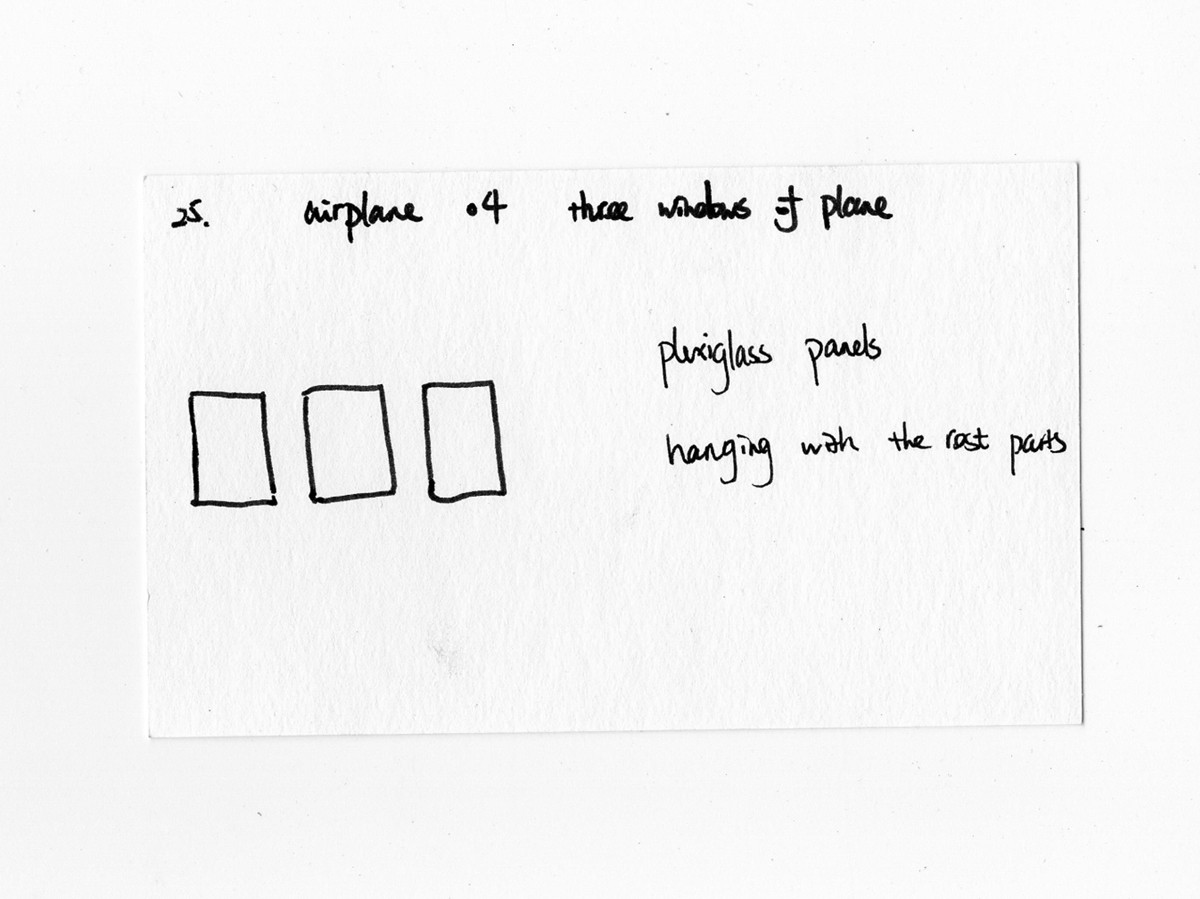

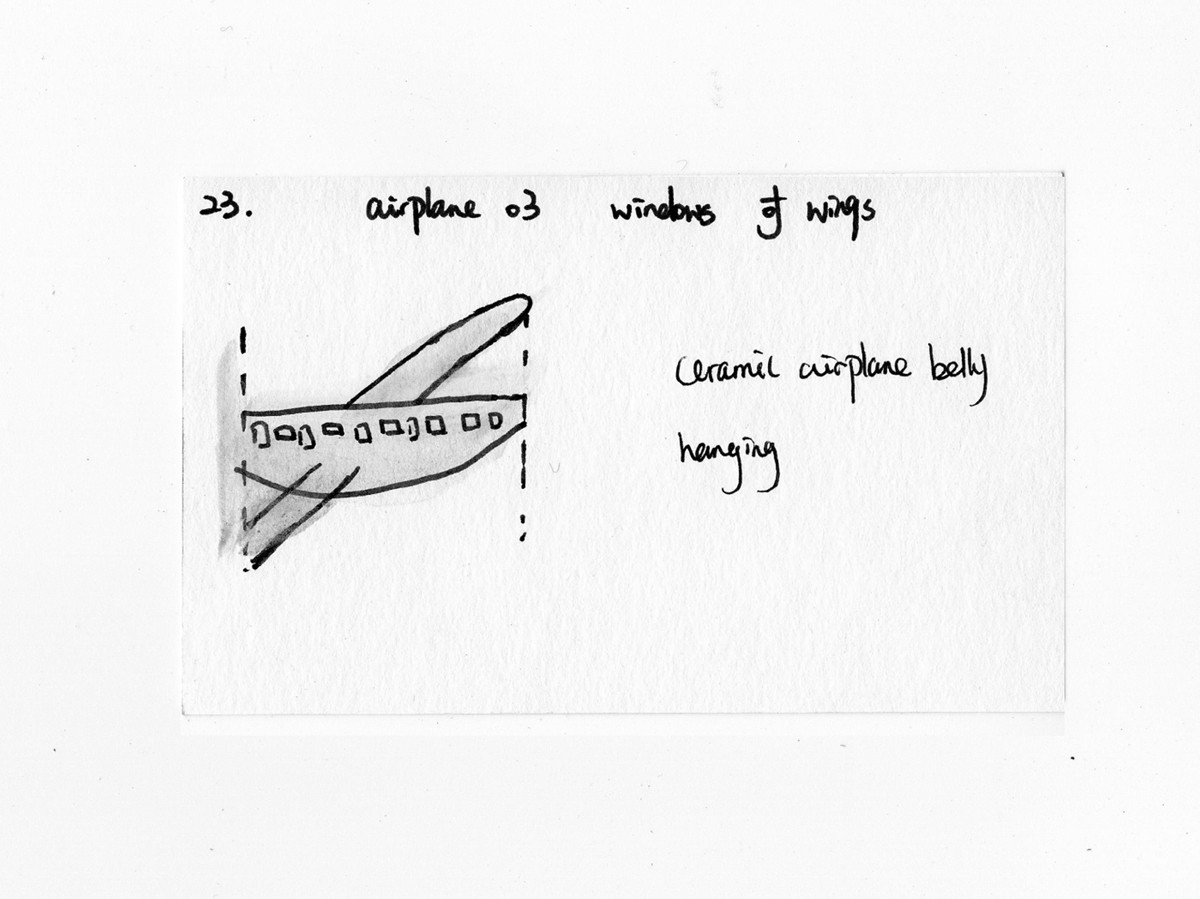

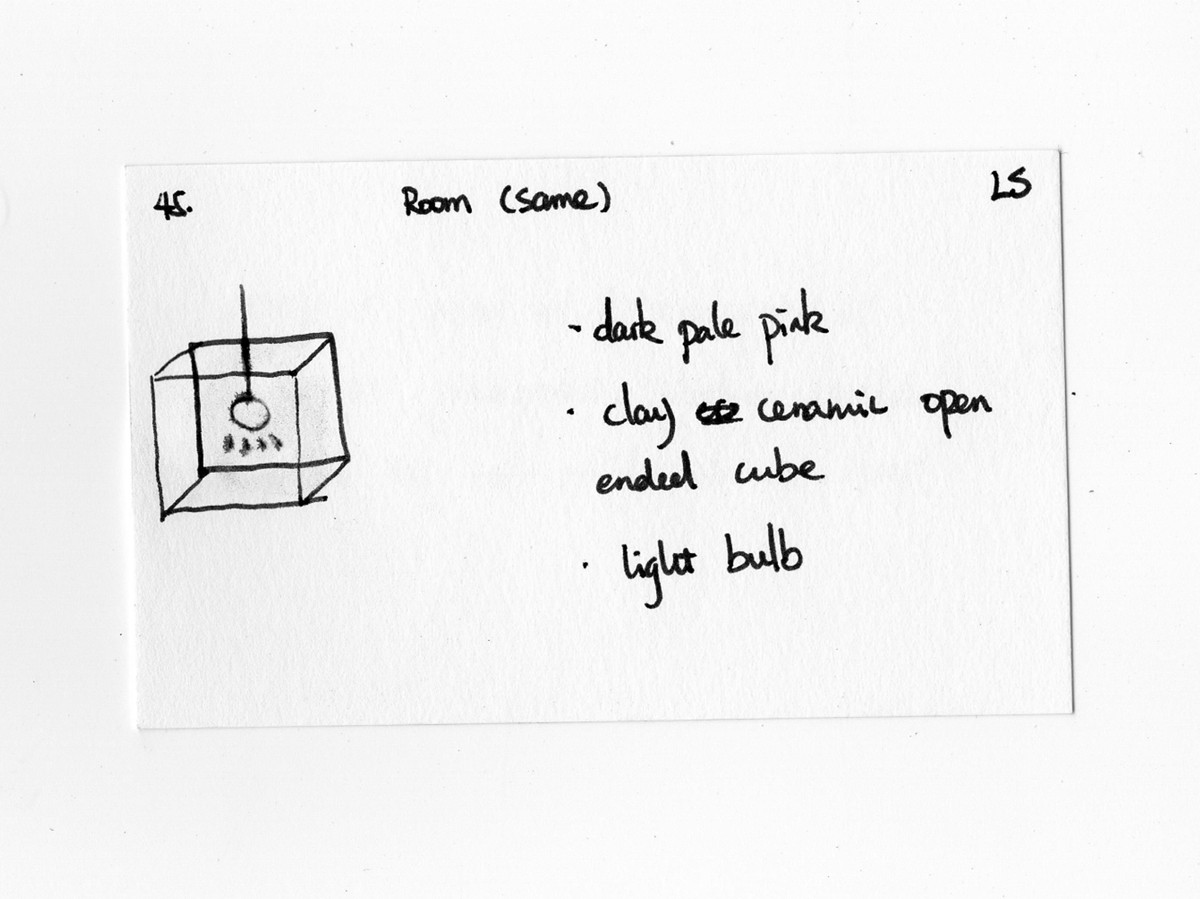

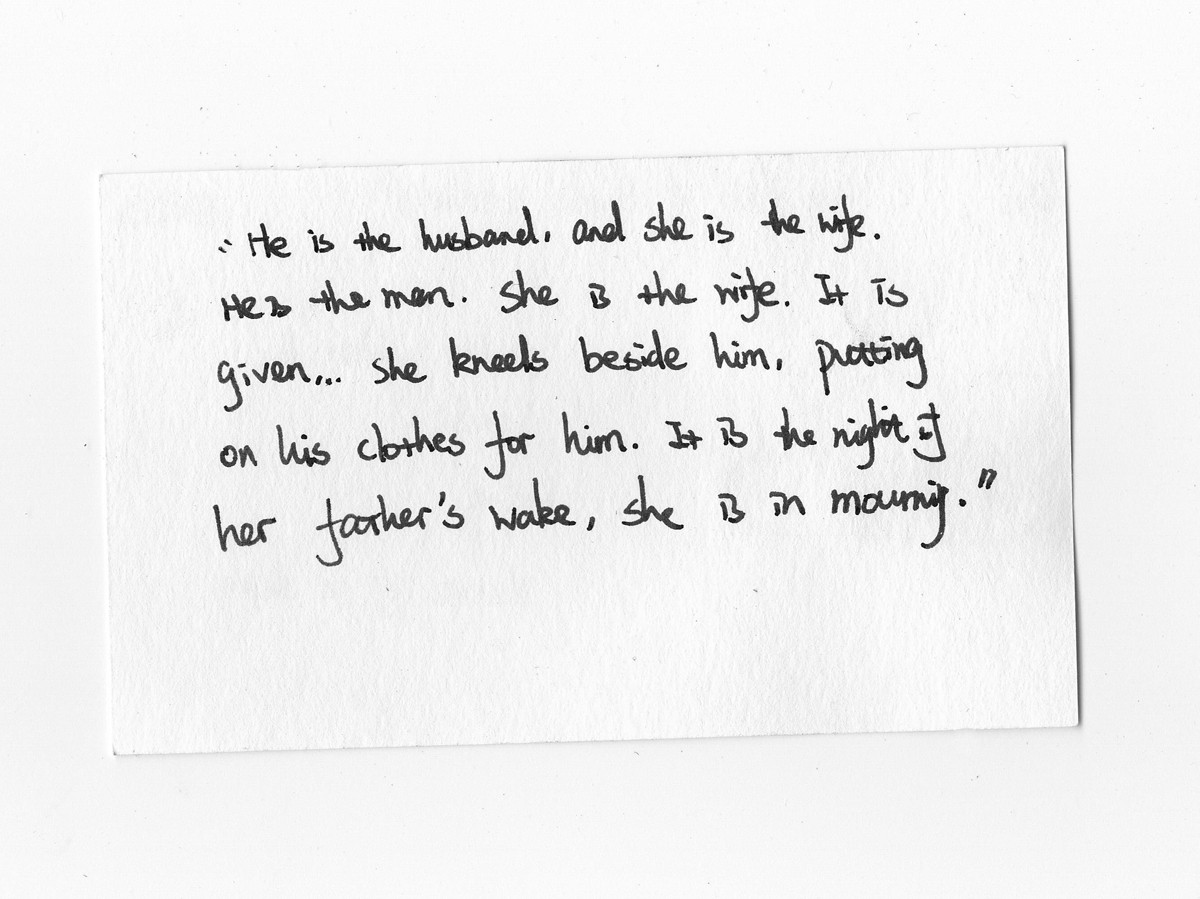

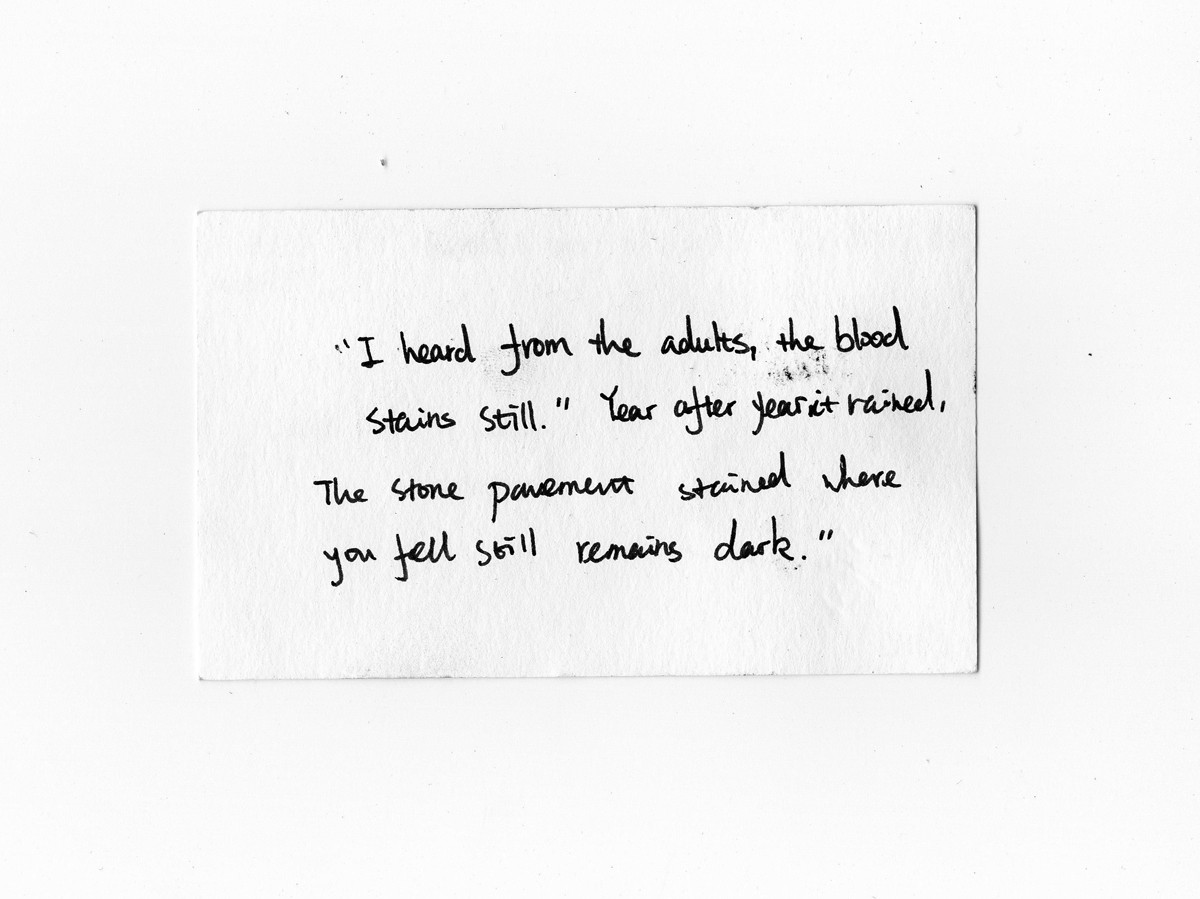

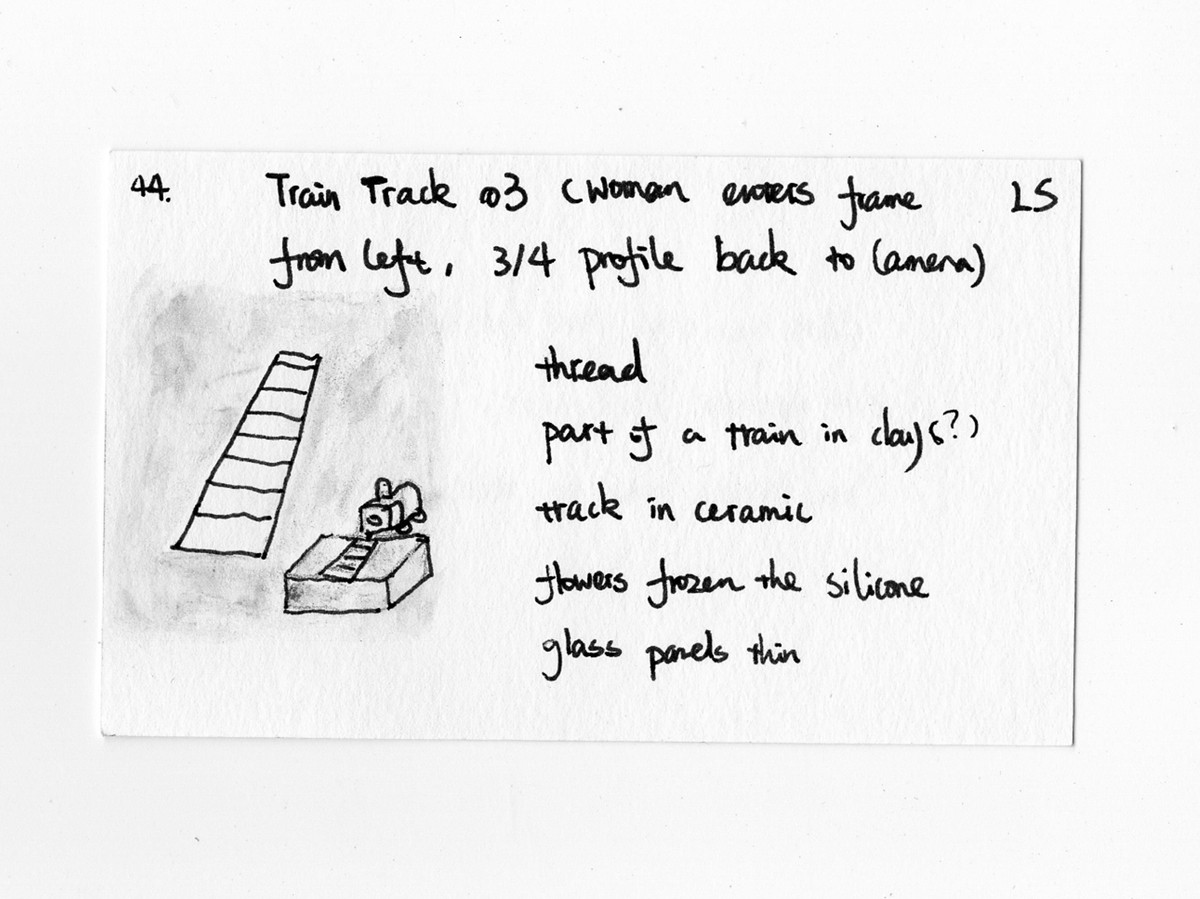

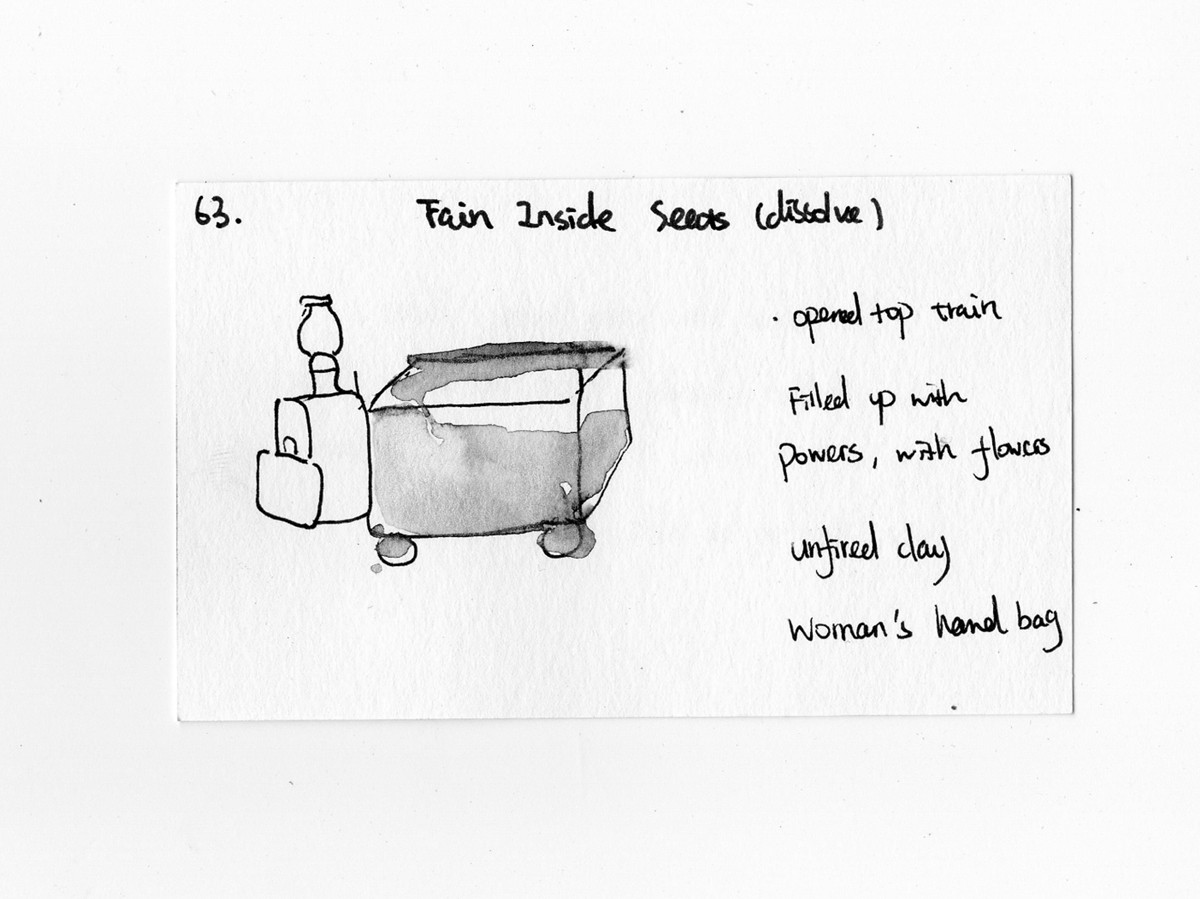

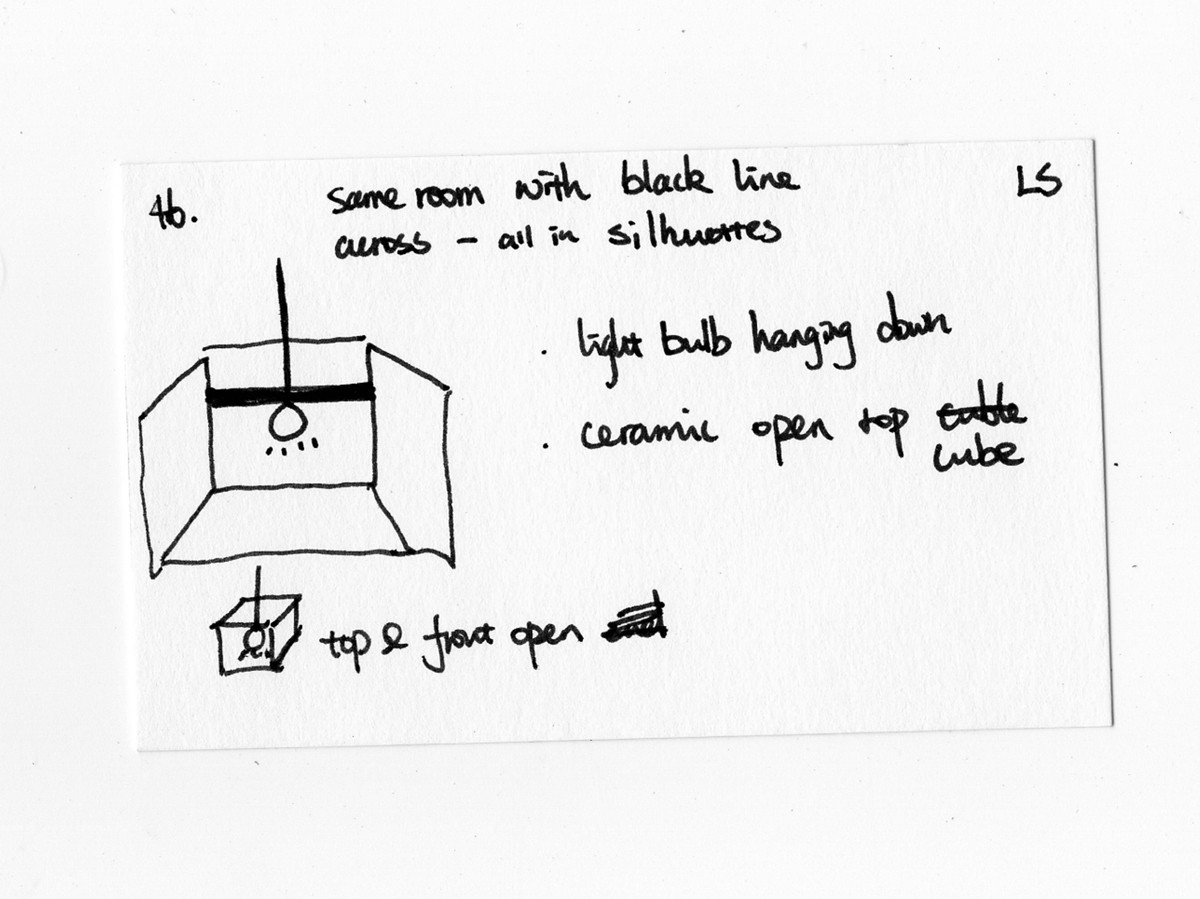

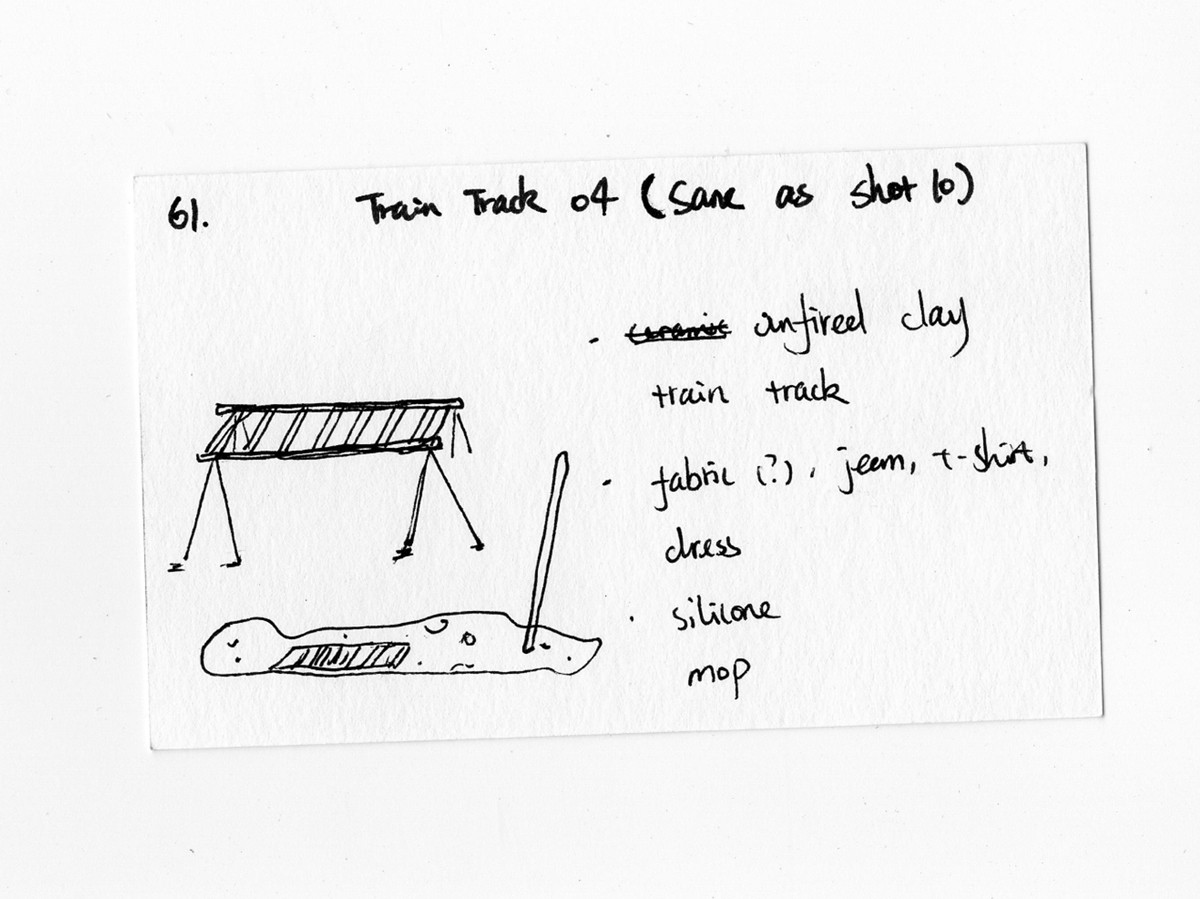

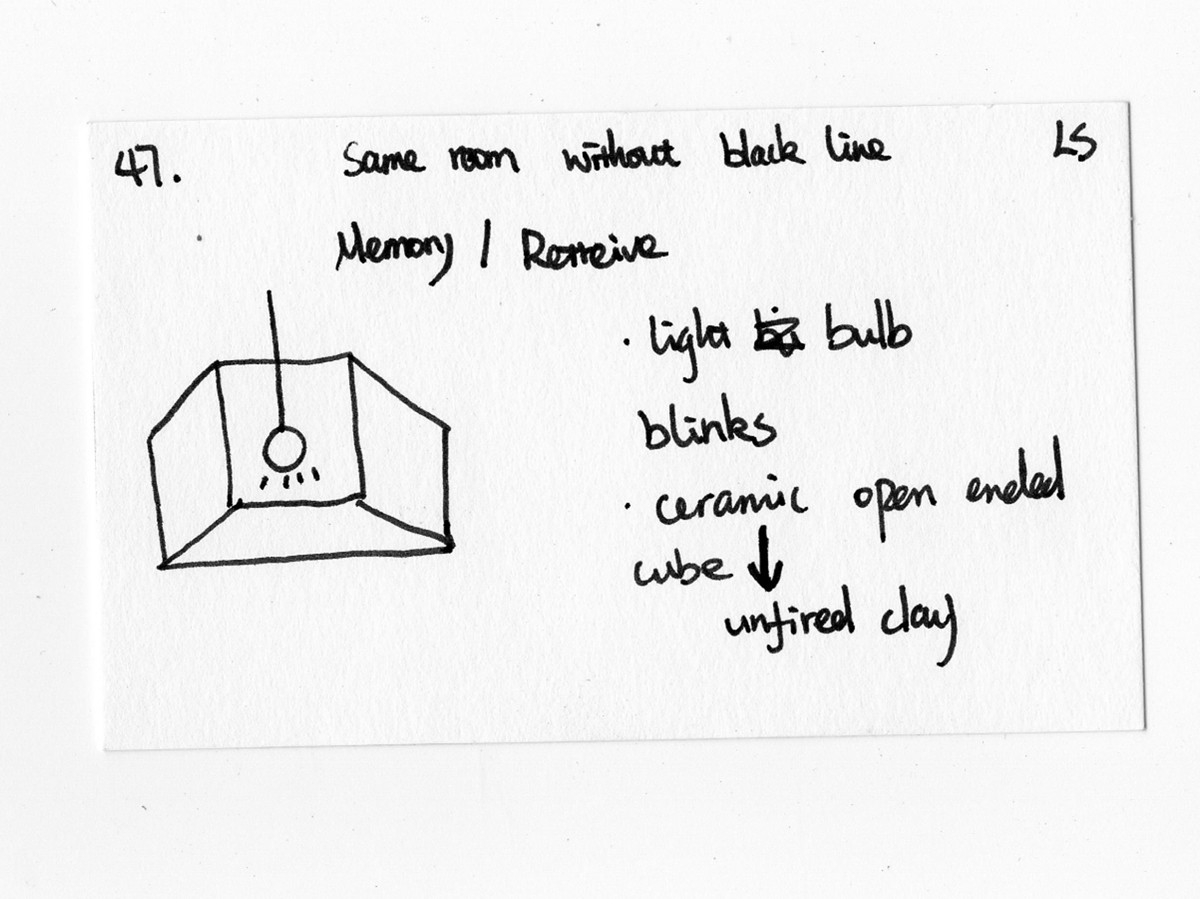

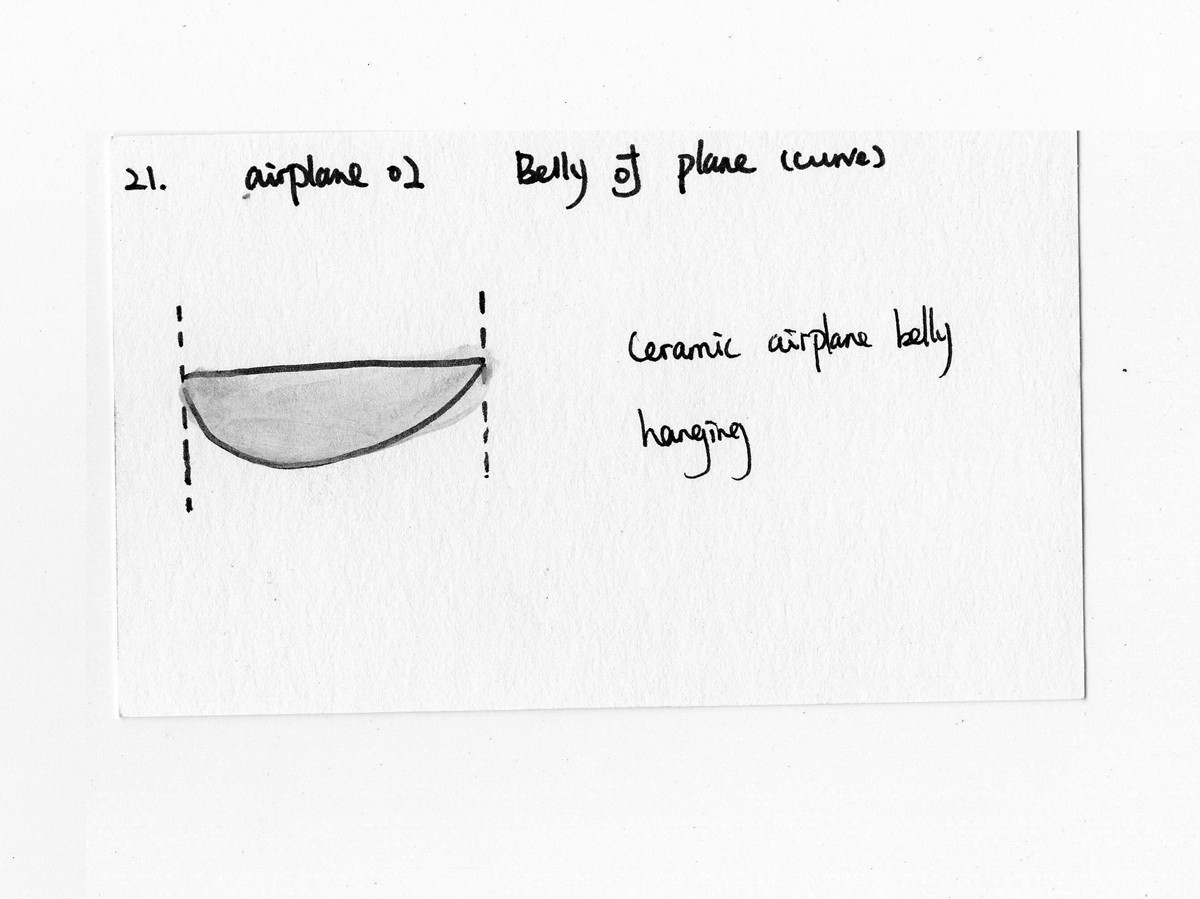

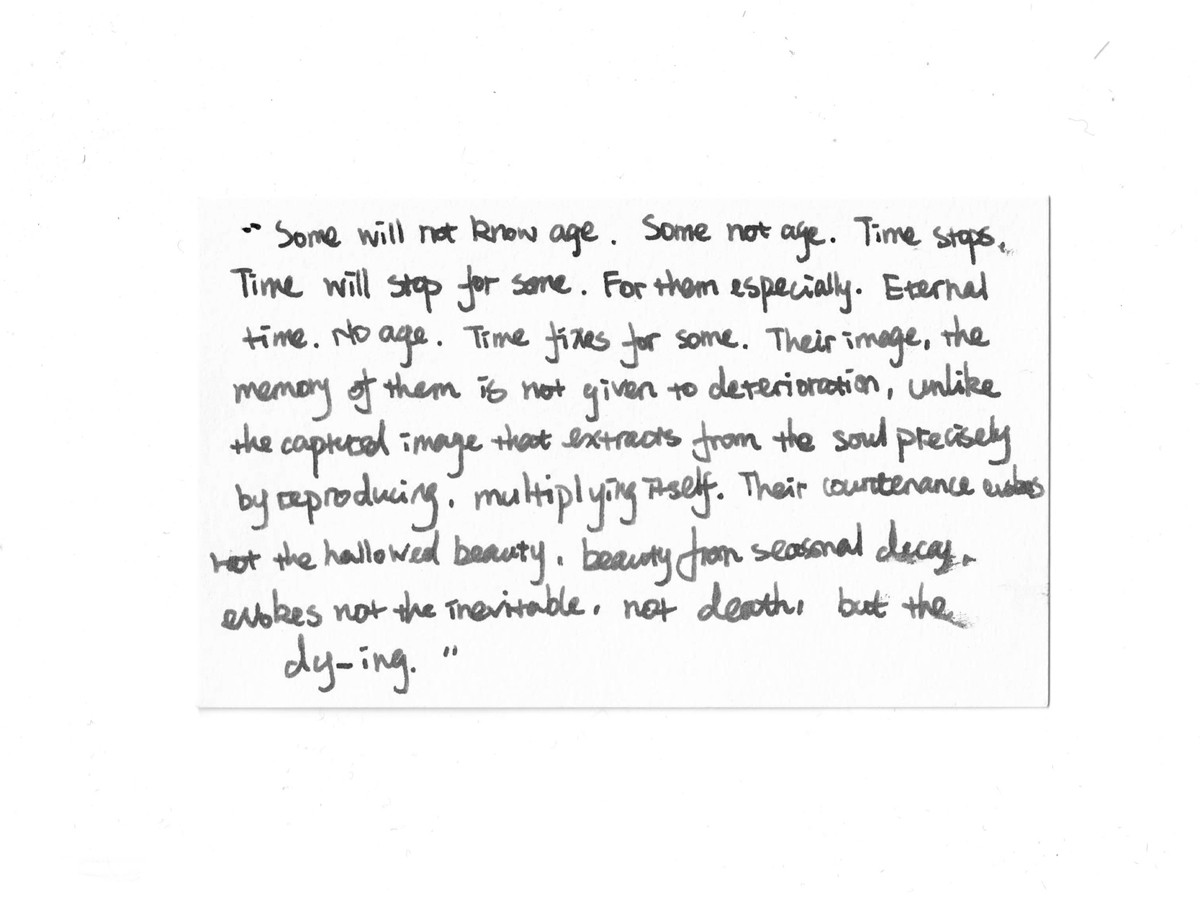

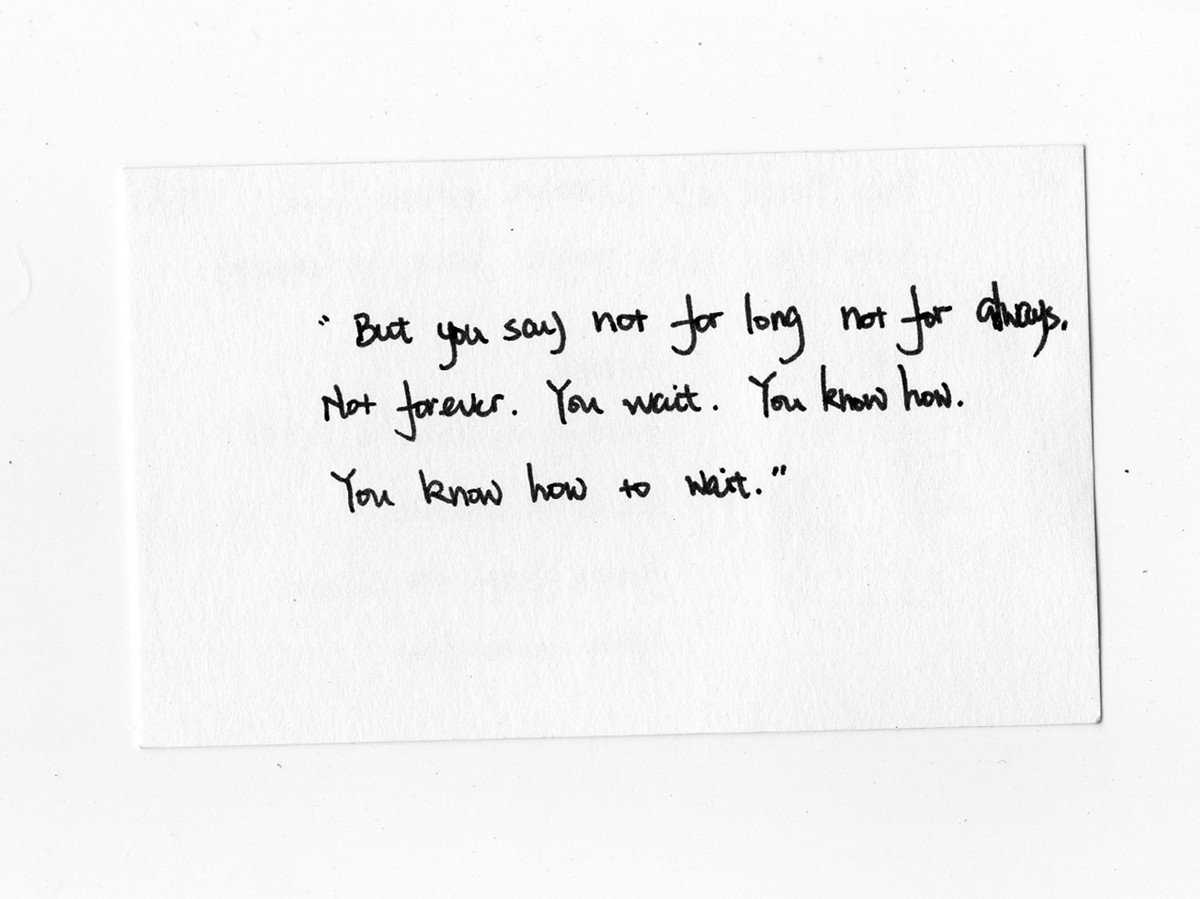

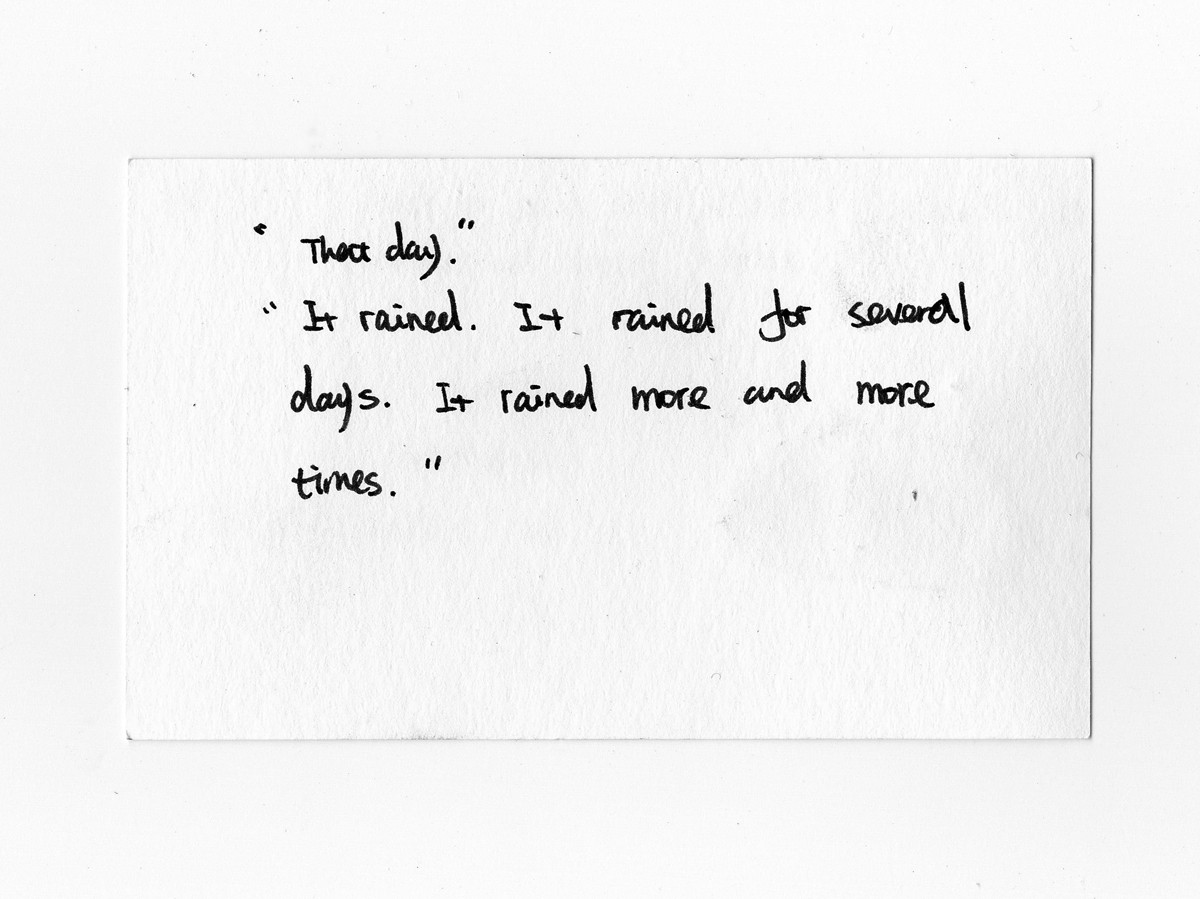

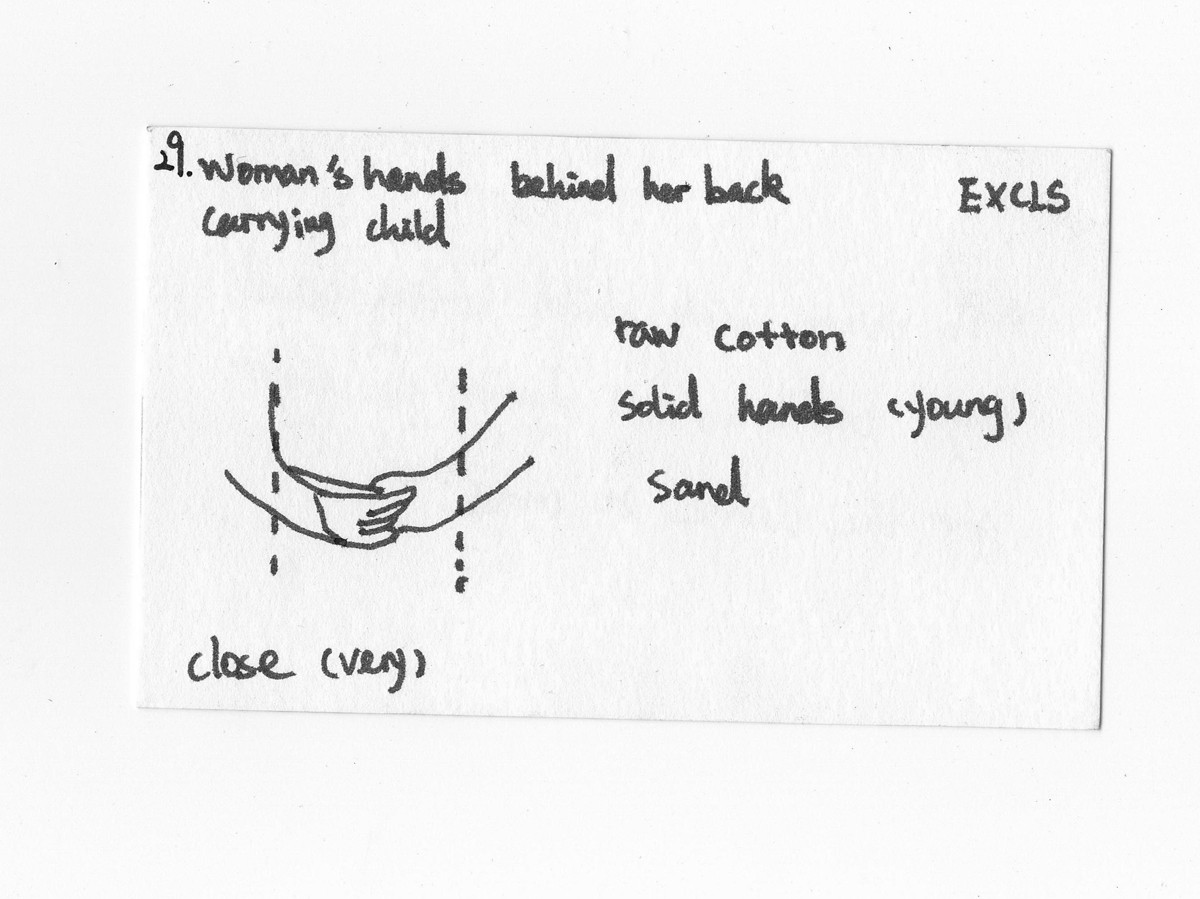

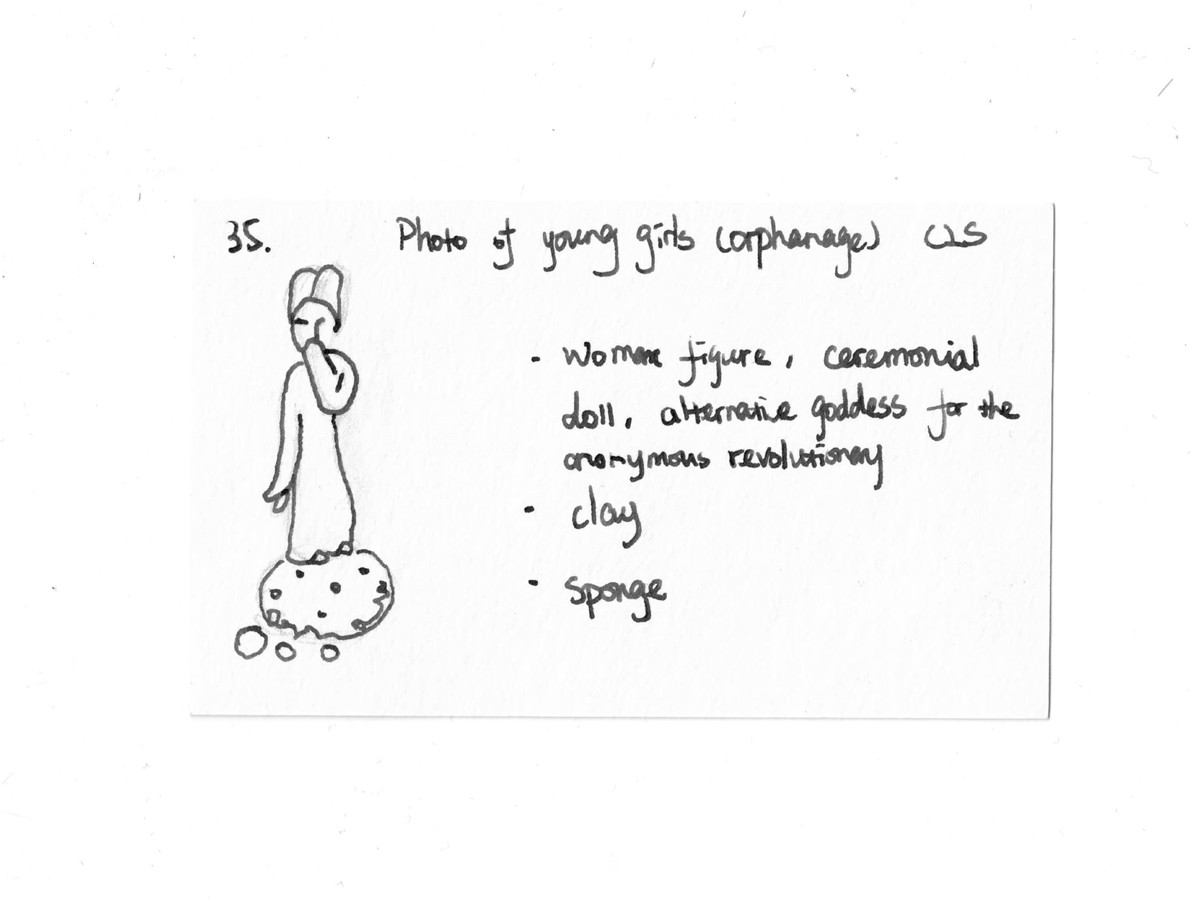

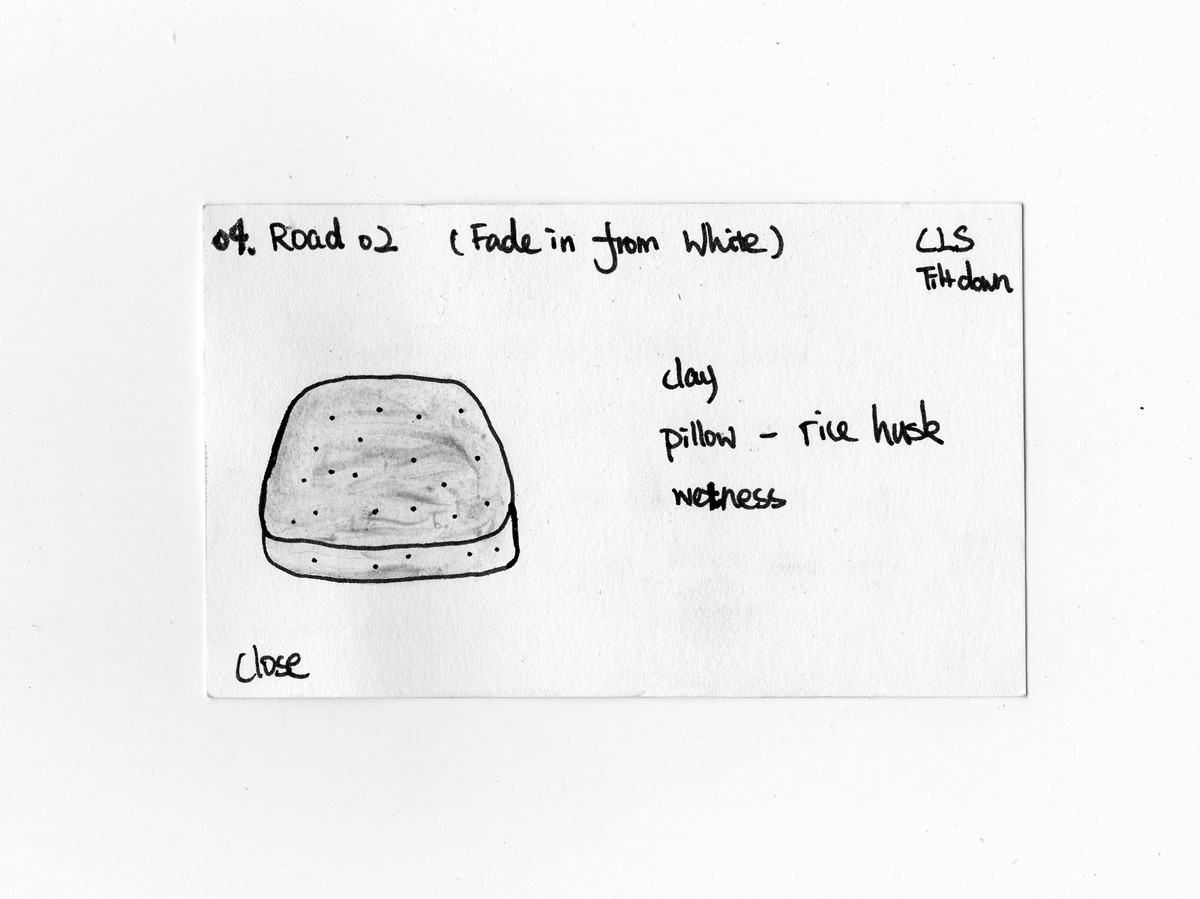

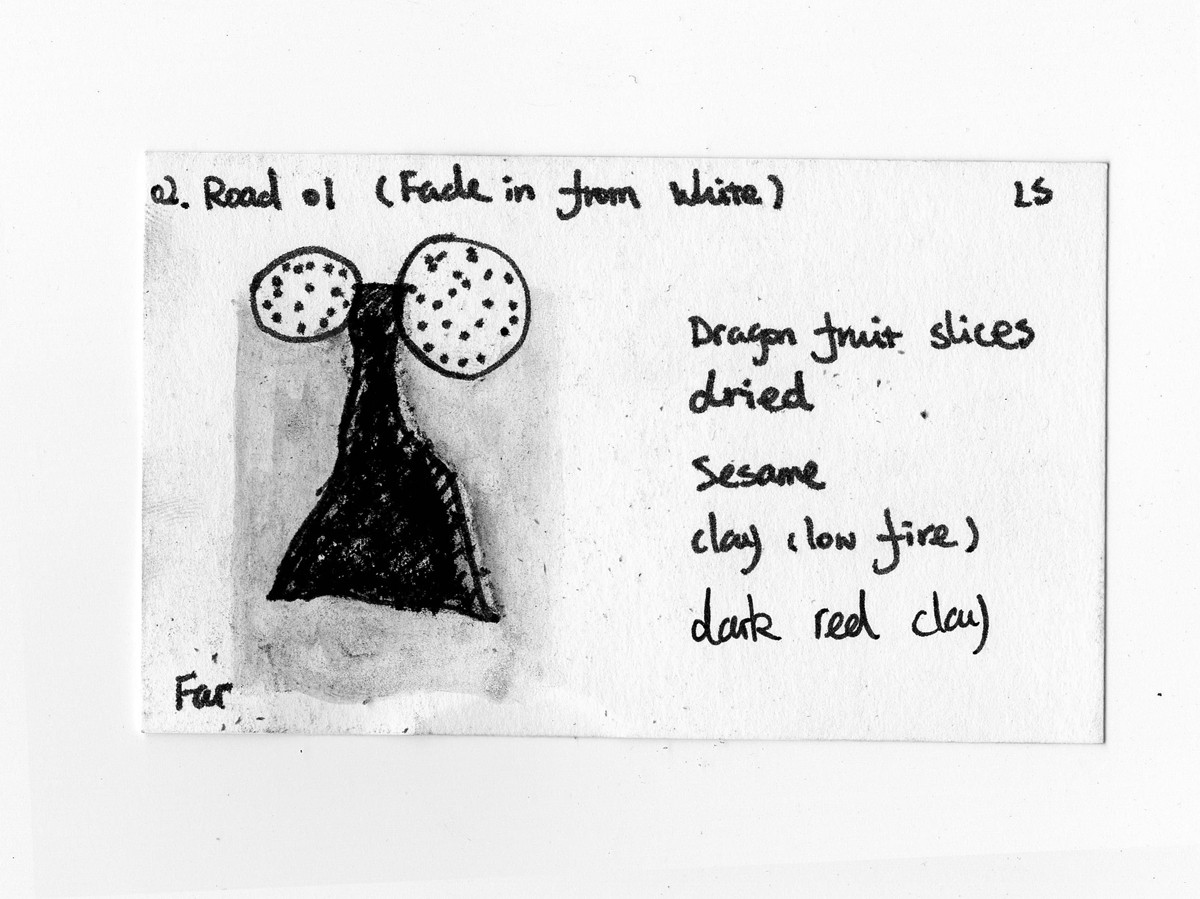

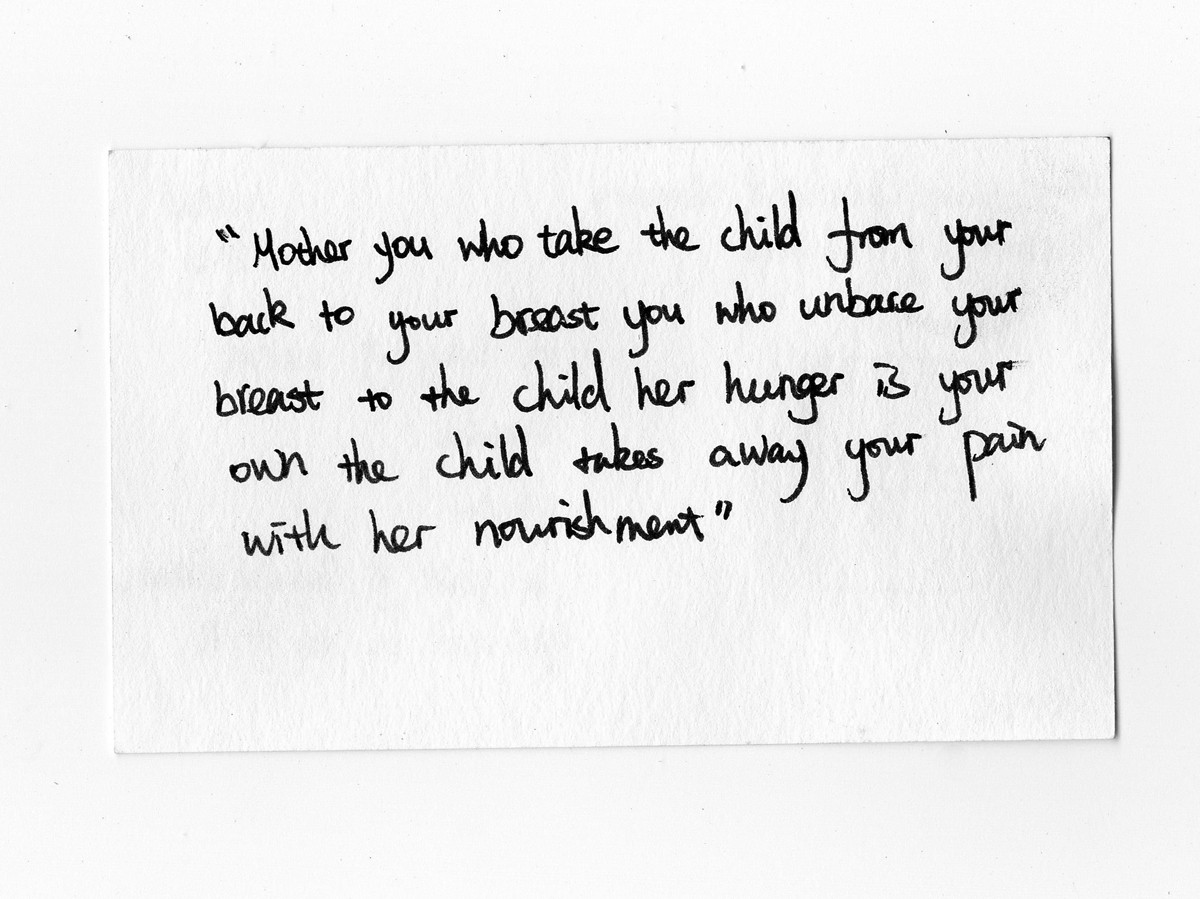

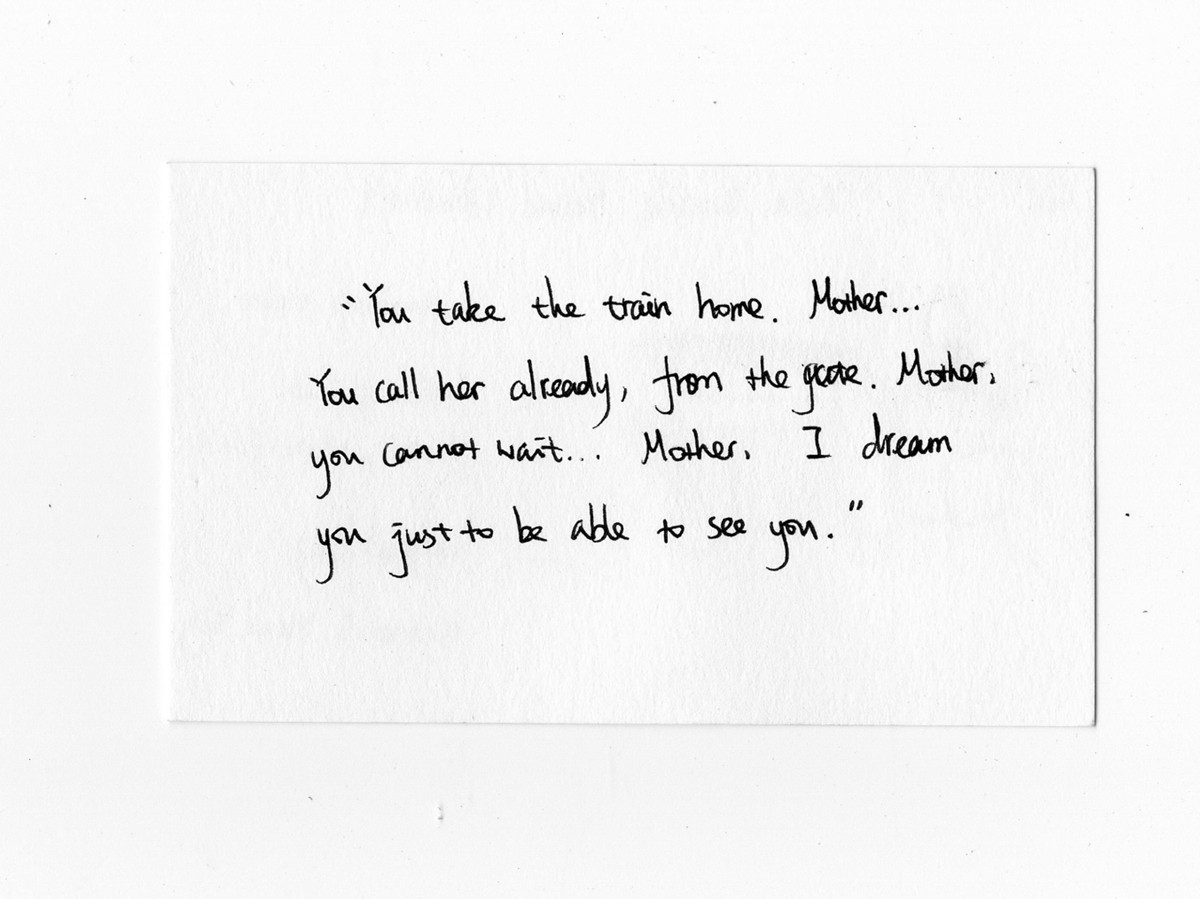

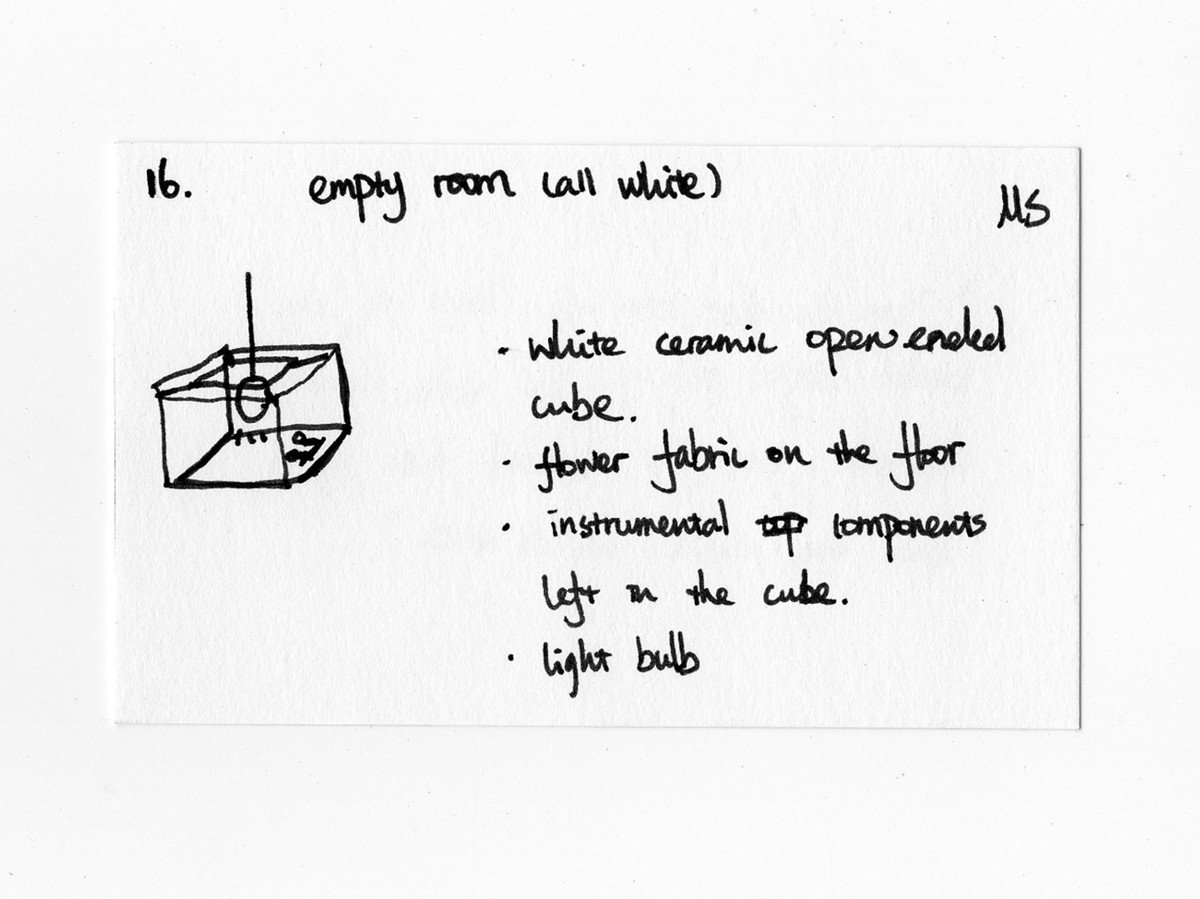

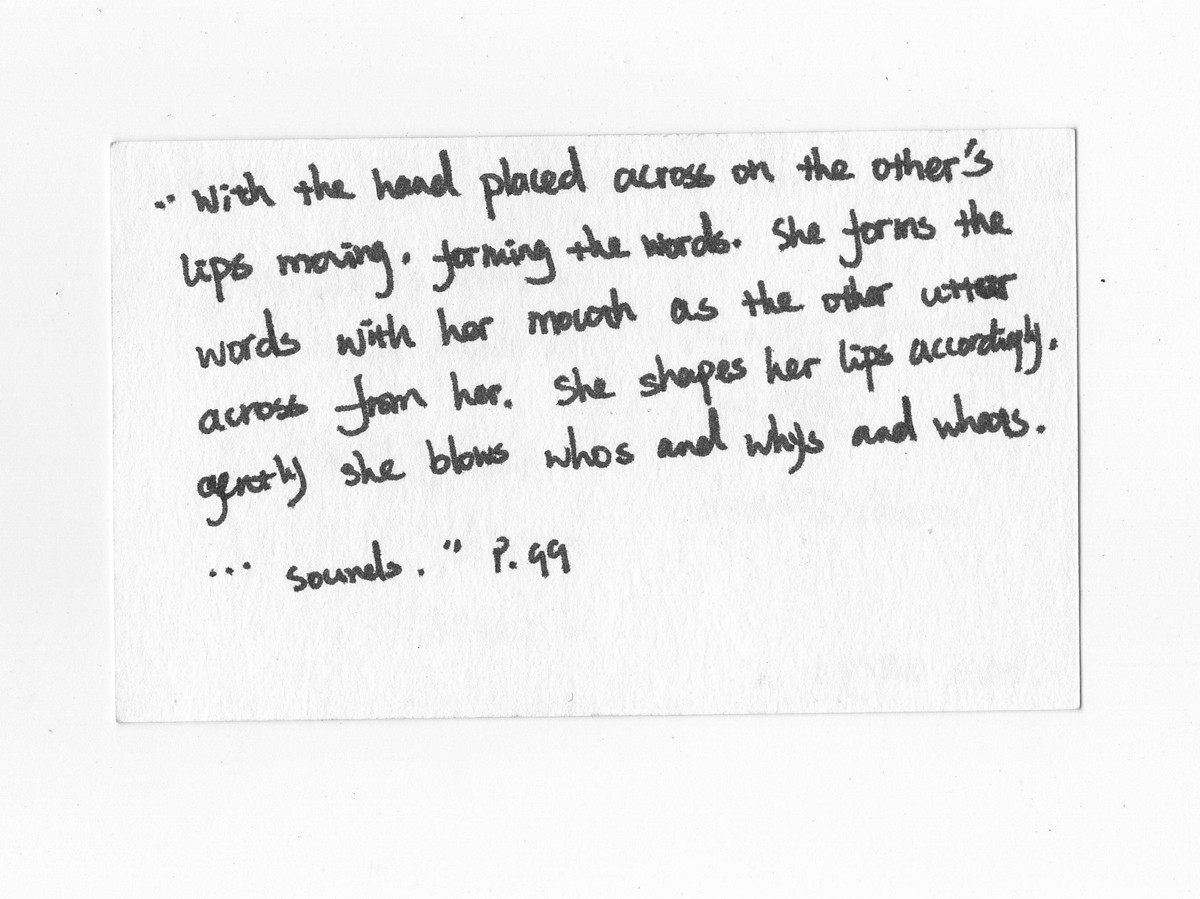

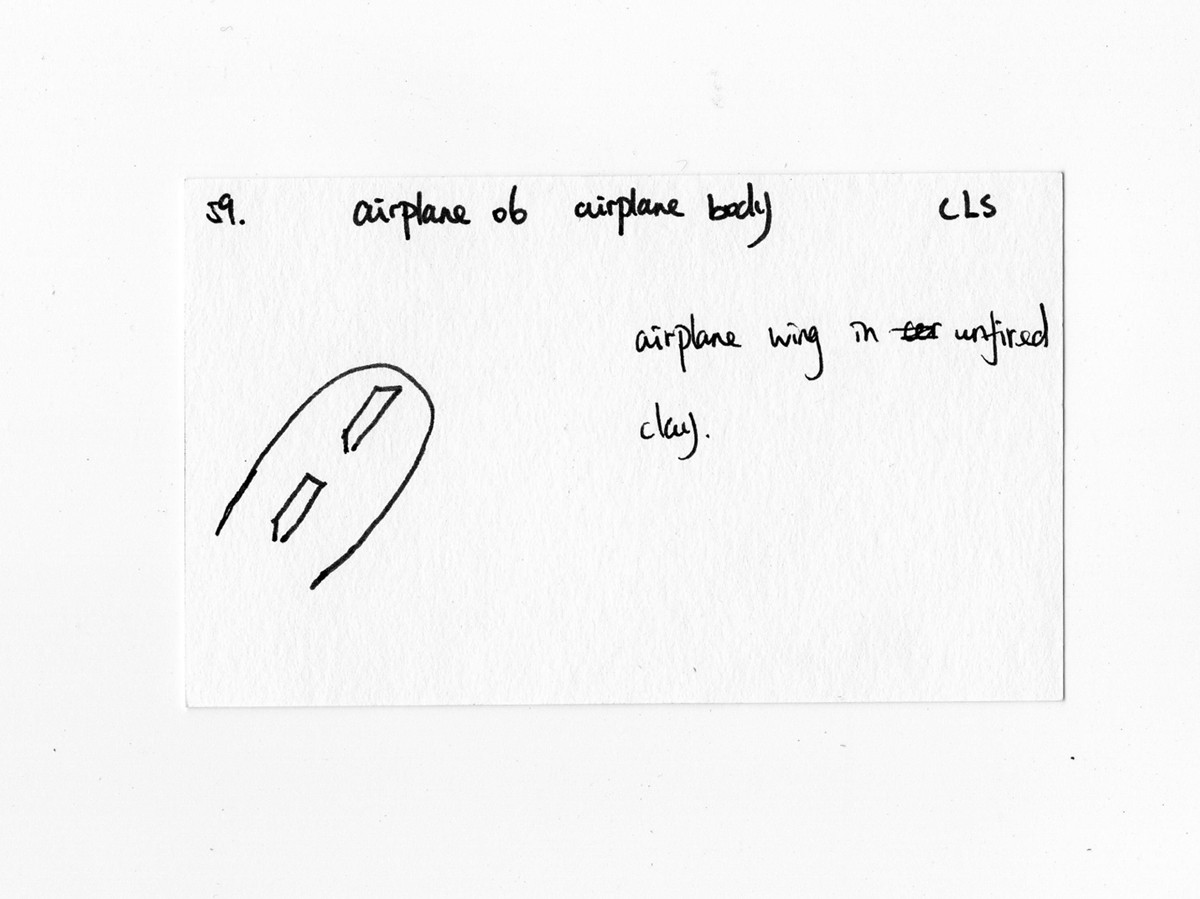

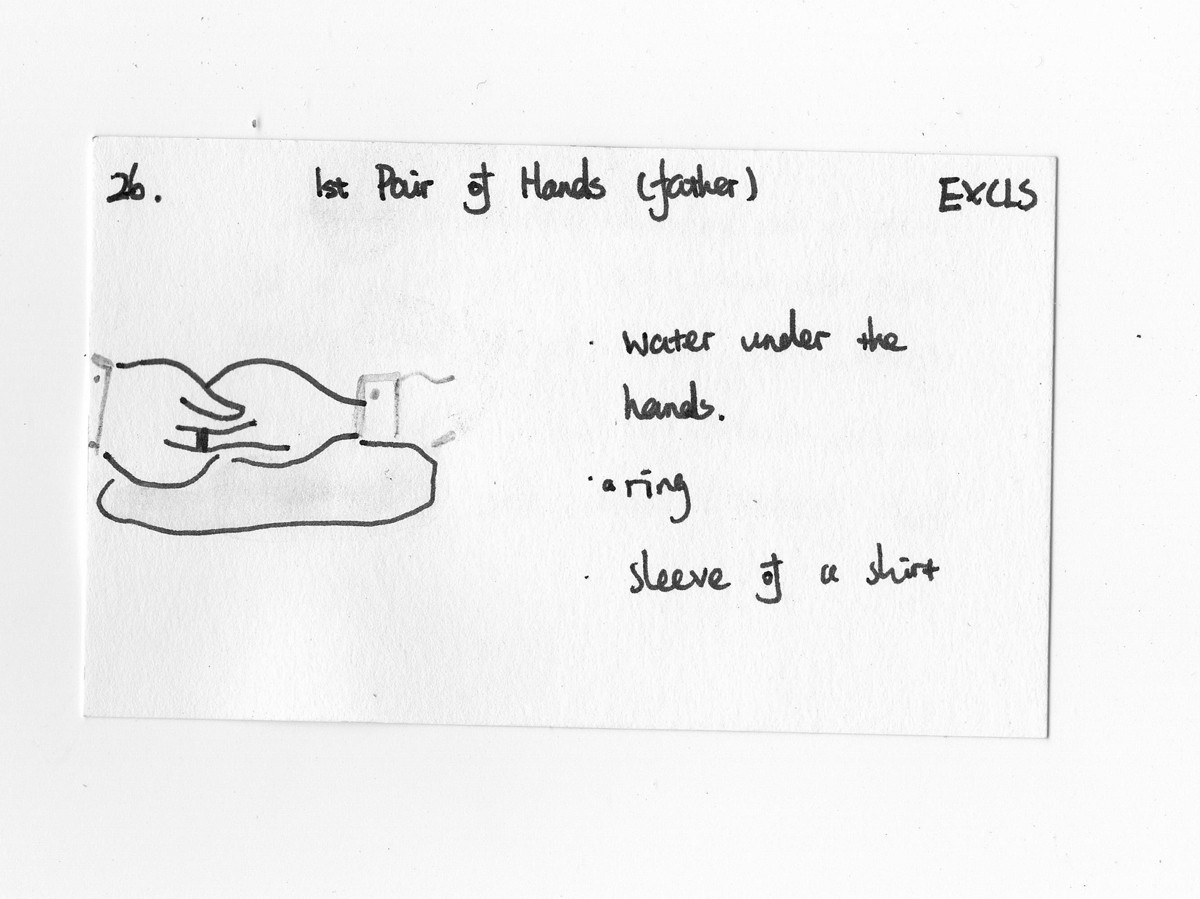

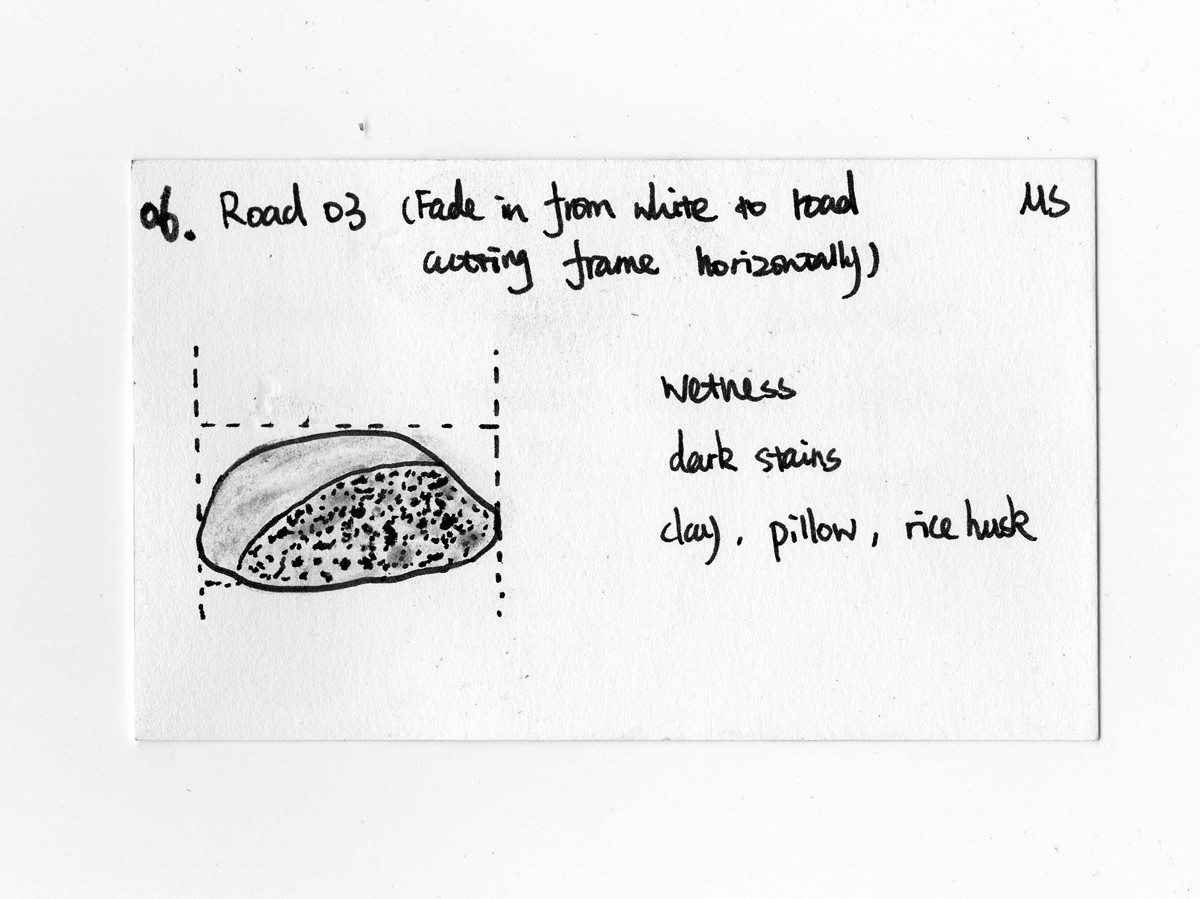

Insofar as Straub-Huillet’s self-insertion into history is always fundamentally a political engagement with the here-and-now, Wu’s encounter with Cha’s work is by no means accidental. Both diaspora female artists, much of their experience resonates with each other, and so does their shared interest in exploring loss, displacement, and disappearance. Cha’s project, entitled White Dust from Mongolia, was never completed due to her tragic death at the age of 31. However, the raw unedited footage, a storyboard detailing the 85 shots, and a written narrative have been preserved at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Wu’s proposal, put simply, is to materialize the unfinished film by studying and transforming the 85 shots into interconnected objects, images, and forms. I should mention here that, although BAMPFA has offered generous support in making these materials accessible, they nonetheless rejected the idea of incorporating any of Cha’s original materials into the reconstruction, for the reason that Wu’s work seems to “intend or appear to presume to speak on behalf of the artist.” One can’t help but be reminded of the fate of Straub-Huillet’s Cézanne film, also rejected by the Muséd’Orsay which had initially commissioned it. Though the position of the institution is certainly understandable, it once again poses the question of authorship back to us.

There is something quite beautiful when Wu offers a solution to this dilemma: instead of using the original materials directly, she creates a machine to capture just the fluctuations of light projected from the images–a receptacle of sensations, a reflection of what cinema is in its very concrete. If the authenticity of an AI’s voice can be questioned as nothing more than a pure reflection of what have been created, it is also right beneath such reflections that we can trace a genealogy of art practice. I would end with a passage from the Aesthetics of Disappearance by Paul Virilio, who amusingly enough, once engaged with Straub-Huillet in a heated debate on image and virtual reality:

The whiteness of birds or that of horses, the brilliant strips pasted on the clothes of experimental subjects, make the body disappear in favor of an instantaneous blend of givens under the indirect light of motors and other propagators of the real. […] the world keeps on coming at us, to the detriment of the object, which is itself now assimilated to the sending of information. […] technique finally reproducing permanently the violence of the accident; the mystery of speed remains a secret of light and heat from which even sound is missing.

Excerpt from “A Disappearing Act,” an essay by Xiaofei Mo published originally in LEAP Magazine, December 2016